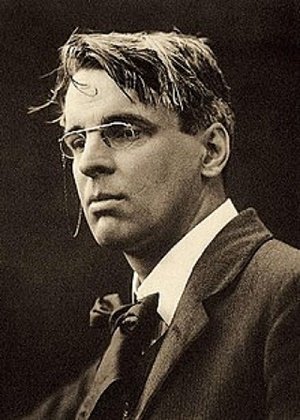

Una figura de importancia en la poesía de habla inglesa del siglo XX es el escritor irlandés William Butler Yeats, fallecido el 28 de enero de 1939, quien recibiera el Premio Nobel de Literatura en 1923. Es reconocido por su labor como poeta y dramaturgo, en las cuales destacó, aunque también escribió ensayos de carácter filosófico.

============

An important figure in twentieth-century English-language poetry is the Irish writer William Butler Yeats, who died on January 28, 1939, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1923. He is recognized for his work as a poet and playwright, in which he excelled, although he also wrote essays of a philosophical nature.

Fuente | Source - Dominio público | Public Domain

Se le reconoce su papel principal en la renovación de la literatura irlandesa, pero también, de manera general, en la inglesa y europea. Tuvo una tendencia muy marcada hacia el esoterismo y el misticismo, que se manifiesta en su poesía, pero sobre todo en sus ensayos y artículos. También tuvo una actuación en política, siendo senador a raíz de la creación del Estado Libre de Irlanda; en política tuvo una tendencia nacionalista y conservadora, llegando a posiciones extremas un tanto desencaminadas.

Fue autor de una extensa obra poética y dramatúrgica, ambas caracterizadas por su convencida tendencia simbolista (sobre ella escribió en sus ensayos), por el mundo mágico –mítico y legendario- y la belleza natural de Irlanda (su tierra, a la que vuelve siempre, atesorando en su corazón el amor por el lar de los abuelos –Sligo–), por las influencias orientalistas.

En teatro, no solo fue escritor de numerosos textos dramáticos, sino también director y promotor: fundó el Teatro Abbey y la Compañía Nacional de Teatro. Entre sus obras pueden nombrarse, Entre siete bosques, Palabras en el cristal de la ventana y Purgatorio.

En su poesía, ya en la etapa última, irá decantando su inclinación simbolista y haciéndose de un estilo más directo y prosaico, como podrá notarse en poemas que reproduzco a continuación, tendencia que se expresará en sus libros El gato y la luna, La torre, La escalera de caracol y Últimos poemas. Haré un comentario general al final.

============

He is recognized for his leading role in the renewal of Irish literature, but also, in a general way, in English and European literature. He had a very marked tendency towards esotericism and mysticism, which is manifested in his poetry, but especially in his essays and articles. He also had a role in politics, being a senator following the creation of the Irish Free State; in politics he had a nationalist and conservative tendency, reaching extreme positions somewhat misguided.

He was the author of an extensive poetic and dramatic work, both characterized by his convinced symbolist tendency (he wrote about it in his essays), by the magical world -mythical and legendary- and the natural beauty of Ireland (his land, to which he always returns, treasuring in his heart the love for the lar of his grandparents -Sligo-), by the orientalist influences.

In theater, he was not only a writer of numerous dramatic texts, but also a director and promoter: he founded the Abbey Theater and the National Theater Company. His plays include, among others, In the Seven Woods, The Words upon the Window Pane and Purgatory.

In his poetry, already in the last stage, his symbolist inclination will be decanting and becoming a more direct and prosaic style, as can be seen in poems that I reproduce below, a trend that will be expressed in his books The cat and the moon, The tower, The Winding Stair and Last poems. I will make a general comment at the end.

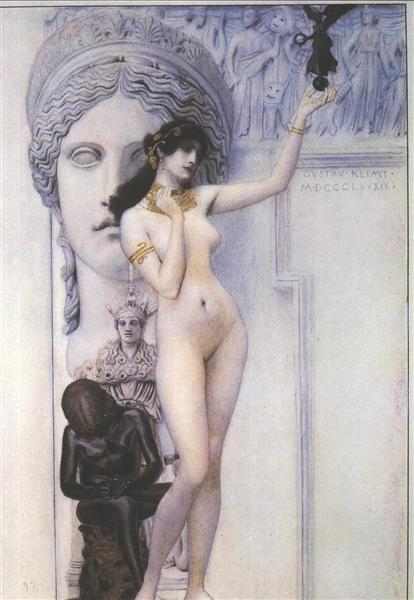

Fuente | Source - Dominio público | Public Domain

El vino entra en la boca...

El vino entra en la boca

Y el amor entra en los ojos;

Esto es todo lo que en verdad conocemos

Antes de envejecer y morir.

Así llevo el vaso a mi boca,

Y te miro, y suspiro.

A Drinking Song

Wine comes in at the mouth

And love comes in at the eye;

That’s all we shall know for truth

Before we grow old and die.

I lift the glass to my mouth,

I look at you, and I sigh.

***

Leda y el cisne

Un golpe inesperado: las grandes alas baten

en la aturdida joven, las oscuras membranas

le acarician los muslos, siente el pico en su nuca

y la opresión del pecho en su pecho indefenso.¿Cómo pueden los blandos, sobrecogidos dedos

apartar de sus muslos la emplumada grandeza?

¿Y cómo puede el cuerpo, envuelto en blancas ráfagas,

no sentir el extraño corazón palpitante?Un espasmo en las ingles engendra con el tiempo

la muralla caída, la torre y el techo en llamas

y la muerte de Agamenón.Tan sometida,

tan domeñada por la sangre bestial del aire,

¿tomó con su energía cierto conocimiento

antes de que el pico indiferente la soltara?

Leda and the Swan

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air,

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

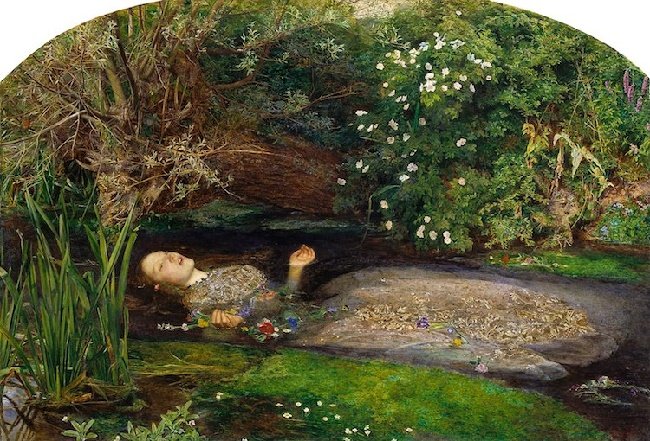

Recuerda la olvidada belleza

Al ceñirte en mis brazos,

estrecho contra mi corazón esa belleza

que del mundo hace mucho se marchara:

coronas engastadas que reyes arrojaron

en charcas fantasmales, huyendo los ejércitos;

cuentos de amor tejidos con hebras de seda

por soñadoras damas en telas que nutrieron la polilla asesina:

rosas de tiempos idos

que las damas tejieron en sus pelos;

lirios fríos de rocío que las damas portaron

por tanto corredor sagrado,

adonde tales nubes de incienso se elevaban

que sólo Dios estaba con los ojos abiertos:

ya que el pálido pecho, la mano demorada,

nos llegan de otras tierras más pesadas de sueño,

y también de otra hora más pesada de sueño.

Y cuando tú suspiras entre besos

escucho la blanca Belleza también suspirando

por aquella hora cuando todo

deberá consumirse cual rocío.

Mas llama sobre llama y hondura sobre hondura,

y trono sobre trono y medio en sueños,

posadas sus espadas en sus férreas rodillas,

tristemente cavilan sobre grandes misterios solitarios.

He Remembers Forgotten Beauty

When my arms wrap you round I press

My heart upon the loveliness

That has long faded from the world;

The jewelled crowns that kings have hurled

In shadowy pools, when armies fled;

The love-tales wrought with silken thread

By dreaming ladies upon cloth

That has made fat the murderous moth;

The roses that of old time were

Woven by ladies in their hair,

The dew-cold lilies ladies bore

Through many a sacred corridor

Where such grey clouds of incense rose

That only God’s eyes did not close:

For that pale breast and lingering hand

Come from a more dream-heavy land,

A more dream-heavy hour than this;

And when you sigh from kiss to kiss

I hear white Beauty sighing, too,

For hours when all must fade like dew,

But flame on flame, and deep on deep,

Throne over throne where in half sleep,

Their swords upon their iron knees,

Brood her high lonely mysteries.

Fuente | Source - Dominio público | Public Domain

Una joven y vieja mujer

¿Cuál fue el alegre muchacho que más me agradó

De todos cuantos yacieron conmigo?

Respondo que mi alma entregué

Y en el dolor amé,

Mas gran placer me dio un muchacho

Al que físicamente amé.

Libre del cerco de sus brazos

Reía al pensar que era tal su pasión

Que él imaginaba que yo entregaba el alma

Cuando sólo existía el contacto de dos cuerpos,

Y reía sobre su pecho al pensar

Que era la misma entrega que hay entre las bestias.

Di lo que otras dieron

Después de quitarse la ropa,

Mas cuando esta alma del cuerpo se despoje

Y desnuda vaya a lo desnudo

Aquel a quien halló encontrará allí dentro

Lo que ningún otro conoce.

Y dará lo suyo y tomará lo suyo

Y regirá por derecho propio;

Y aunque amó en el dolor

Tanto se aferra y se cierra,

Que ningún ave diurna

Osaría extinguir tal deleite.

IX - A last confession

What lively lad most pleasured me

Of all that with me lay?

I answer that I gave my soul

And loved in misery,

But had great pleasure with a lad

That I loved bodily.

Flinging from his arms I laughed

To think his passion such

He fancied that I gave a soul

Did but our bodies touch,

And laughed upon his breast to think

Beast gave beast as much.

I gave what other women gave

’That stepped out of their clothes.

But when this soul, its body off,

Naked to naked goes,

He it has found shall find therein

What none other knows,

And give his own and take his own

And rule in his own right;

And though it loved in misery

Close and cling so tight,

There’s not a bird of day that dare

Extinguish that delight.

***

Muerte

Ni miedo ni esperanza

aguarda el animal la muerte;

cuando a su fin se acerca el hombre,

todo lo espera y todo teme.

Muchas veces ha muerto,

y volvió a alzarse muchas veces.

Asentado en su orgullo el hombre grande

frente a los asesinos, escarnece

las amenazas de cortar su vida;

Él conoce la muerte,

la conoce hasta el tuétano.

El hombre creó la muerte.

Death

Nor dread nor hope attend

A dying animal;

A man awaits his end

Dreading and hoping all;

Many times he died,

Many times rose again.

A great man in his pride

Confronting murderous men

Casts derision upon

Supersession of breath;

He knows death to the bone—

Man has created death.

Difícil comentar breve y condensadamente poemas tan profundos y vigorosos. Quise presentarlos seguidamente, sin comentarios, para propiciar la experiencia que nos da la lectura poética sin cortes, más allá de los que provee nuestra sensibilidad y pensamiento.

¿Qué decir? Son poemas, en mi apreciación, de una belleza única, tocados por ese sentido rítmico muy propio de la poesía anglosajona, que no siempre, por supuesto, las traducciones pueden conservar. Hay en ellos, en unos más que en otros, una vena irónica que los hace muy propiciadores de la interpretación abierta, aspecto que me parece definitivamente muy atractivo y característico de su modernidad.

Resaltaría la sensualidad de la visión hecha palabra, con imágenes sensoriales –sencillas o complejas–, bien sea por el gusto del vino y el amor, por la posesión y éxtasis de Leda, por la vejez femenina que se remoza en el recuerdo del placer, o por esa recuperación memoriosa y afectiva de la belleza inasible y enigmática, que hace a la vida.

Y finalmente, el hermoso poema a la muerte, ante el cual no tenemos palabras.

============

It is difficult to comment briefly and in a condensed form on such profound and vigorous poems. I wanted to present them in the following, without comments, in order to propitiate the experience that gives us the poetic reading without cuts, beyond those provided by our sensibility and thought.

They are poems, in my opinion, of a unique beauty, touched by that rhythmic sense very typical of Anglo-Saxon poetry, which, of course, translations cannot always preserve. There is in them, in some more than in others, an ironic vein that makes them very conducive to open interpretation, an aspect that I find definitely very attractive and characteristic of their modernity.

I would highlight the sensuality of the vision made word, with sensory images -simple or complex-, either by the taste of wine and love, by the possession and ecstasy of Leda, by the feminine old age that is soothed in the memory of pleasure, or by the memory and affective recovery of the elusive and enigmatic beauty, which makes life.

And finally, the beautiful poem to death, before which we have no words.

Referencias | References:

Yeats, W. B. (1983). Poesía y teatro. España: Ediciones Orbis.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Butler_Yeats

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._B._Yeats

https://www.biografiasyvidas.com/biografia/y/yeats.htm

http://amediavoz.com/yeats.htm

https://www.festivaldepoesiademedellin.org/es/Revista/ultimas_ediciones/93/yeats.html

https://www.poeticous.com/yeats?locale=es

Gracias por su lectura | Thank you for reading.

The rewards earned on this comment will go directly to the people sharing the post on Twitter as long as they are registered with @poshtoken. Sign up at https://hiveposh.com.

Gracias por la ilustración @josemalavem me pareció muy buen post, muy completo, yo desconocía sobre este literato anglosajón. Gracias por compartirlo. Exitos

Gracias a ti por la visita y tu omentario. Saludos, @pedroerami.

Para eso estamos José, un abrazo fraterno

Interesante aporte, hermano, desconocía de este autor, lo tendré en cuenta para leer algunas de sus obras. Captó bastante mi atención. Gracias por compartir. Un abrazo desde Venezuela.

Agradecido por tu visita y comentario, @diegoguedez. Ojalá puedas leer algo de él; en las referencias hay enlaces que ofrecen selección de su obra poética. Saludos desde Cumaná (Venezuela).