Hello Hivers and Book Clubbers,

High time for another book review. Last review, I said that we'd probably be moving on to South African history. That turned out to be wrong: we stay with that of Germany. The book I'm reviewing today is fully titled 'Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia 1600-1947'. It was written by Australian historian Christopher Clark, and first released by Penguin in 2006. The story proper amounts to almost 700 pages, so it's quite the read. Let's get into it.

What is Prussia?

Let's start by laying down the basics, because I would've needed them too 10 years ago. Back then, when I read 'Prussia' for the first time, I was pretty certain someone mis-spelled Russia for some reason. But no, Prussia is a distinct entity, and it isn't Russia, but German.

Prussia is the kingdom (before 1701 it was a duchy) of the Hohenzollern dynasty, who started out as a small-time princedom in the south of Germany. In 1417, the Hohenzollerns were able to buy the Electorate of Brandenburg (capital: Berlin) from the Habsburg emperor.

This turned out to be an investment for the ages, though it was not for the obvious reason: Brandenburg itself was a region without serious industry, without big cities (Berlin was a small provincial town at the time) and with poor agricultural soil. But the prince, from then on, held the title of Elector, and was thus one of the seven men in the Holy Roman Empire who was able to choose the next emperor.

In large part, these elections were a formality; the Habsburgs formed an unbroken chain of Emperors through several centuries. Yet the position held power, and favours could be asked during every election in trade for the vote that was held with the electorate.

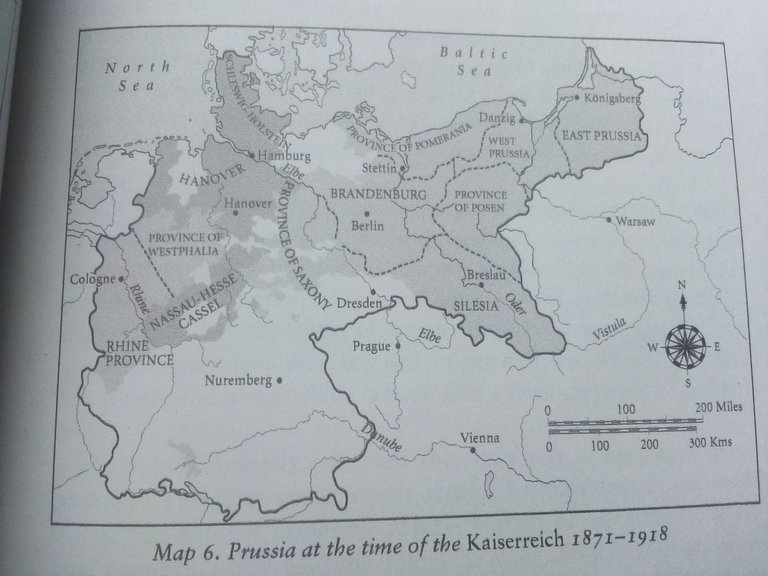

Over the first centuries (15th to 17th) of Hohenzollern rule in Brandenburg, several small territories were acquired, which I won't go into here. One was of far bigger importance, which came from a different branch of the Hohenzollern family tree: East Prussia, with its capital Konigsberg (today: Kalinigrad), was a German-speaking territory far to the east of Brandenburg situated on the Baltic Sea (see map for reference).

This used to be the seat of the Teutonic Knights, whose mission it was to force Christianity upon the peoples to the east of them, chief among them the Lithuanians. One of the last Grand Masters (Hochmeister) of the Teutonic Knights was a Hohenzollern, before it became a more secular title under the Kingdom of Poland. This branch of the Hohenzollerns combined with the other into a total force that was becoming one of the stronger players in the Holy Roman Empire. Something the Habsburgs would not appreciate, surely.

Frederick the Great and the Power-Grab

King Frederick II of Prussia (ruled 1740-1786) is one of the big names in European history, yet I'm unsure if most people can place him in the correct time-frame and European situation. Frederick did not play around on the world stage, and made a power-play that would be of significant impact on German, and thus European history.

The Habsburgs had a problem: the then-emperor only had daughters, and the Salic (French) inheritance laws used by the Habsburgs at the time meant that only sons could inherit. They tried to execute an exemption, which became known to history as the 'Pragmatic Sanction' (strange name). This meant that the eldest daughter, Maria Theresia, would inherit all the Habsburg domains in Central Europe, which should be considered from then on as indispensible Habsburg patrimony.

Yet most of Europe salivated at the idea of gaining a part of that patrimony, and pretenders and claimants stood up everywhere: Frederick did not really have a serious claim to anything, but he did have a well-trained and disproportionately large army. And he was daring. So he simply invaded Silesia in 1740 (see map above), and kept it. This was Austria's richest province, and also rich in iron, a very important resource at the time.

The Habsburgs would try to retake Silesia in the Seven Years War (1756-1763) , but without success: the Prussian army held on to the central core of its territory, even though it faced the Austrians, the French and the Russians at different intervals during this war. The power-balance had shifted: Prussia was now a power that counted, and would be a rival to the Habsburgs within the Holy Roman Empire from then onwards.

One empire gone, another takes its place

Problem was, the Holy Roman Empire was in its final decades at the time. Napoleon would end it in 1806. Prussia itself was threatened as well; yet it stuck through, and during the Congresso of Vienna in 1815, it was 'rewarded' with the Rhineland in West-Germany. Not a land of great importance at the time, but with the start of the Industrial Revolution in Germany a few decades later, the Ruhr would become synonymous with German industrial power, which was almost unrivaled in the world at the time.

Both the strengthened army and developing industry would combine with the diplomatic genius of Otto von Bismarck, chancellor (i.e. prime minister) of Prussia. His career (1862-1890) was extremely successful. In two wars he would forge what would become the German Empire, one that easily surpassed the Austrian one in power. Those Austrians were first beat in 1866, and after that, the French were beat so hard that they became a Republic again in 1871.

Conclusion

The Kingdom of Prussia would thus become a part, albeit the dominant one, of the German Empire from 1871 onwards. Within this structure, it would go through both World Wars, until it was dissolved by decree by the Allies in 1947. The name 'Prussia' would be left to the history books.

This book itself, of course, tells a lot more than I just did. It goes onto the more cultural side of things, it tells about the rulers in more detail, about other wars I haven't mentioned, about religious differences etc. etc.

It's a good all-round read for someone looking into German history, and I picked up a lot of new things as well; I didn't know much about Brandenburg in the 17th century, before it became a kingdom in 1701. I'll be back with more reviews in the future. Until then,

-Pieter Nijmeijer

(Both photo's are self-taken images from the book cover and illustrative map)