In my last post in the series, I gave a few examples of what is considered art, or rather, good art, and some lively discussion ensued - all good stuff even if we didn’t all agree.

And I don’t suspect we will all agree in the end, but I think even asking the questions and engaging in discussion is really worth the effort to define this for ourselves as consumers and possibly makers of art in different forms.

Today, I’d like to talk about that nebulous topic: beauty

What Is Beauty?

I’m going to operate on the premise that beauty is a requirement for good art. Beauty is not just something that is pleasing to the eye or the ear: in the culinary world, that would probably mean anything sweet is beautiful. But don’t we love something savory too like a juicy piece of steak? Or what about things that are sour or tangy, like pickles or a glass of kombucha?And don’t forget salty potato chips!

All of these things are aspects of beauty within the culinary world, and when done “well” - a term I will define a bit later - they invoke a feeling in the beholder of that art. And this will transform them in some way.

Objection 1: ”This all sounds well and good, but can you really define aspects of art?”

If aspects of good art could not be defined, then there would be no popular works.

If you think about it, it’s pretty amazing that a person can put together colors and textures on a canvas, and that blob communicates something to a person they’ve never met before and invokes a feeling in them. And if it’s “good” or “done well,” then a large number of people agree.

But it’s more than just a popularity contest, otherwise the latest #1 hit “artist” on the charts would be considered on par with Leonardo da Vinci. I contend also that the work must stand the test of time. The longer the time in popularity, the better the art, or the more effective it was. Just to be clear, I don’t refer to time as a year or two, but decades at least.

The Beatles are a prime example. While not one of my favorite bands, I do like some of their music and I appreciate what they’ve done musically and lyrically. And they’ve reached a lot of people and continue to. I teach 6th graders who are now just discovering them and wanting to play their music on the guitar. There’s got to be something there.

And yet, I don’t necessarily choose to listen to them. “But wait,” you say, “if they are obeying these principles of good art, then how can you not like them?” There is room for personal preference. I love classical music. I like other music, too, but classical reaches me in a way some other music doesn’t - and not all the time. And it is different for each person. See, there is still plenty of room for subjective points of view, even for artists who “obey” the principles of art.

And while I’m sure there are people who wouldn’t choose to hang the Mona Lisa on their wall at home (and that’s not just because they’d get arrested for stealing it), they can see how cool of a painting it actually is and appreciate it.

An artist may adhere to these principles of good art, but that does not necessarily guarantee they will be liked by everyone, but at least if it's not liked, it won't be because they lacked skill at their craft - it will be because that person doesn’t like that genre, or prefers another style.

Principle Number 1: Structure

Using nature as our model, everything has structure. There is a reason for everything being in a certain place, and there is organization at every level: think of the structure of a cat. Even down to the cellular level there is order and structure.

With this principle in mind, let’s take a look at two pieces of art:

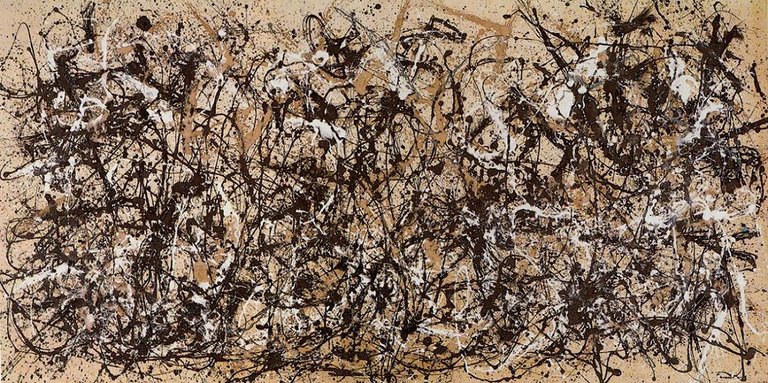

Exhibit A: Autumn Rhythm (Number 30), 1950 by Jackson Pollock

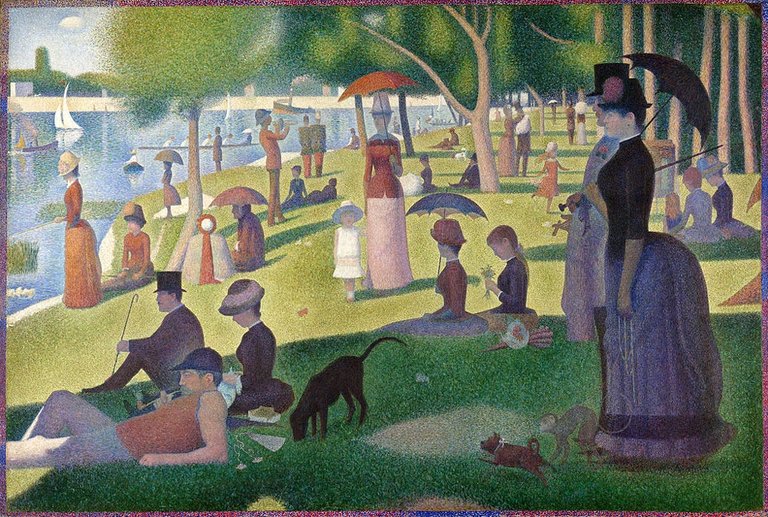

Exhibit B: A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884 by Georges Seurat

Both of these paintings contain many similarities:

- Oil on canvas

- Lots of variety in colors used

- Texture through many dots of paint

But I do think this is where the similarities end. In the Pollock painting (Ex. A), there is a distinct lack of structure. In fact, no attempt was even made to make it look like anything. It was left up to chance as to how the paint splattered on the canvas. While Pollock did choose to thin his paint down and also he made choices as to what paint colors to use, there was very little intentionality beyond that to try and create a painting of…something.

In the Seurat painting (Ex. B), however, we see that the entire thing is made up of tiny little dots, each color chosen to create the illusion of people in a park. While not everything is very clear or realistic looking, we can see people, trees, pets, boats, etc. It is clear that the painter fully intended to create the structure of the painting, and I think that upon seeing how it is made up of tiny dots, it’s pretty amazing to think of the work involved in doing that and actually pulling it off successfully.

But How Does It Make You Feel?

Regardless of whether you admire Exhibit B for the technical abilities or not, I think that’s just an added bonus one gets to enjoy as a viewer of this art. The crux of the issue is how ultimately the art makes you feel.

Does the Pollock painting invoke any feelings in you? What about the Seurat?

Personally, I look at the Pollock painting and don’t feel any change. I could look at it and walk away and feel ambivalent. Maybe a little upset that this is considered good art when I see a lot of good artists not getting their art sold, but the painting itself doesn’t change me. I remember it, vaguely, but that’s about it.

The Seurat painting, however, brings me into that world. I see how life might have been in the late 1800s, sure, but what really works about this is that I actually feel calm and relaxed looking at it, as if I were at the park as well. It’s not really an intellectual thing, but a more visceral thing that I don’t get from Autumn Rhythm.

Another Comparison of Structure

Exhibit C: Three Compositions for Piano, 1943, by Milton Babbitt

Exhibit D: Dreaming, from 4 Sketches, Op. 15, 1892 by Amy Beach

Now this is a bit trickier to work out, since the first composition (Ex. C) actually is a highly structured piece of music - on paper. It uses the compositional device of 12-tone serialism, whereby the composer will use all 12 tones of the chromatic scale are played before repeating any one of those 12 tones again (Source). It is also written in ABA form, where A represents one musical idea, and B represents another contrasting musical idea. But by listening, you cannot detect this form.

So like the Seurat painting, it’s cool in its technical prowess, but that coolness factor doesn’t necessarily make you feel anything. And so part of where that feeling comes in is in its perceivable structure.

Compare it with Amy Beach’s piece (Ex. D). While perhaps a less simple structure than the ABA form of the Babbitt piece, one can hear the form much more clearly. We have the first idea that repeats at 1:38 with an alteration at 3:11 that carries it to a new idea, etc.

So while a more complicated structure, there is structure on the micro-level that is more easily understood. The same accompaniment figure exists throughout most of it, and there is a melody that is recognizable so the listener doesn’t feel lost. This, I believe, is what the Babbitt piece is missing, and what ultimately makes his music much less accessible.

Conclusions

One thing I didn’t point out is that I am comparing art from different style periods. You may have noticed that both the Pollock painting and the Babbitt piano piece are from mid-20th century, and that the Seurat painting and the Beach piece are both from the late 1800s. While I agree they are definitely a different aesthetic, I don’t think we want to excuse away the fact that these are clearly not having the same impact on the audience.

I believe structure - one that can be perceived - is incredibly important to the overall impression of art and beauty in art.

What are your thoughts? Is structure important, and why or why not?

I welcome your thoughts and discussion on this topic, as I feel debating these things are beneficial to helping to define them for each of us personally.

In case you missed it, here's Part 1: Introduction.

If you enjoyed this post, then I did my job well. I write posts on...well, does anybody really care? Follow me and find out, upvote what you like.

Very insightful and interesting and well written. I wonder how many artists would agree with your principles, and how that agreement lines up with their own work.

Like, I'd assume that the Pollocks of the world today would wholeheartedly disagree with your statements, and would instead want to define some other standard of critiquing.

Still, objectively...your principles feel right :)

And the thing is, the Pollocks and many other modern artists are achieving popularity today. But will future generations centuries from now agree that this is worthwhile art? Will they want to look at that and study it just as much as Rembrandt?

We shall see, but I suspect not. I think that now it's become a matter of the emperor's new clothes. Everyone says how good it is, and they are even people who are authorities (allegedly) on the subject. People who are not authorities or want to seem like they are, will agree with them.

This is not what I mean by being enjoyed by the masses, and this is why time is a very important factor. Once the artist is long dead, there's hardly any reason to cow tow to them, so then people will only enjoy it if they really want to.

I believe art from mid-20th century still may be too soon to tell.

I think one of the problems you have in your definition is that you're using, what I consider, to be the worst word. "Good." It's the vaguest word we use every day. Good person, good idea, tastes good, feels good, you're a good guy. All completely different meanings. Moral, potentially useful or inspiring, pleasing to the taste in at least one of many different ways, pleasing to to tactile or emotionality in at least one of many different ways. useful or dependable.

Good in most cases is defined as relative. Often subjective. "That was a good movie." "Why was it good?" "Because I really liked it!" Totally subjective.

You argue that there must be something definitive about good art because it becomes popular. You then say that it takes more than that. And must pass the test of time. But you haven't defined "good" yet. I also don't believe in a "test of time." What does that mean exactly? It has to sit around for a while and people have to keep agreeing about it for it contain worth?

Let's talk about the real reason that the art world has critics and rates and ranks pieces of art. Money.

How do you as a person, sell something, if it has no definite value? The art of selling is about creating perceived value in the mind of the buyer.

To me art is not a means to an ends, it is an ends in itself. It is expression. The spirit(no I'm not getting religious or supernatural, it's a scientifically measurable thing) speaking out. I don't think any part of it is reliant on what other people have to say about it afterwards.

You raise some good points. The use of any subjective word, unfortunately, is unavoidable when talking about art. It is a judgment, and at the end of the day, "beauty is in the eye of the beholder."

But as I pointed out, there does have to be something to a piece of art or music that is appreciated by lots of people over several different generations and cultures. How is this even possible? Is it by chance that these same people like the same thing, or is there something more universal to the human experience that overrides our of individual tastes and personalities?

I totally agree that art is an expression. And it is uniquely human to express - no animals do this unless trained. And we do not live in a void - cultures all over the world are by their very definition groups of people, and our art can be and is enjoyed by one another.

When I play a song I've written for someone, I want them to love it. I want them to get the same enjoyment out of it that I do. When they do (and they don't always, sadly), then my joy in what I've done is heightened. I truly believe art is expression, but that it is also meant to be shared. Not everyone agrees, of course, but, hey, it's my opinion. :)

Wow!!! You're really a genius. Your post is extremely perfect I really learnt a lot from it. It is inspiring and educative. I can't afford to be missing this beautiful and intelligent pose. I have decided to follow you so as to learn more from you.

Thank you!

Great post, and glad to see you picking this up again. Food is a good analogy. A person could throw a bunch of random ingredients together in a flurry of passion without preparation and skill. And it would taste like pig slop.

A skilled chef could create a culinary delight even if they move relatively quickly in the kitchen and don't follow a recipe. But that is only because they have prepare their ingredients ahead of time, and because they have the skills to pull it off. (a combination of talent, training, and practice)

However, place the average joe who can only toast bread in an "Iron Chef" competition, even in a good kitchen with all the right equipment and ingredients. He may come up with something slightly edible, but it won't taste good. It certainly won't taste amazing.

Why is it that these same rules don't apply to art? Our taste buds can't be duped into thinking something tastes good when it doesn't.

Somehow, though, we have duped our "artistic tastebuds" through education and exposure of mediocre, sub-par visual and auditory creations into accepting art that is terrible. We call it good.

I don't know. Maybe if a guy was in a dungeon and ate only moldy crusts of bread every day, he might be trained into thinking a McDonald's hamburger is filet mignon.

I think this is probably one of the roots of the problem. There are people in educational circles that teach that mediocre is good, and they indoctrinate their students.

I also think there is a big movement of anti-intellectualism and anti-craftmanship in the arts. Very often now people in general don't recognize skill in something, or worse, they disdain it. As if being skilled is offensive or doesn't add to the artistic value, and I believe it does.