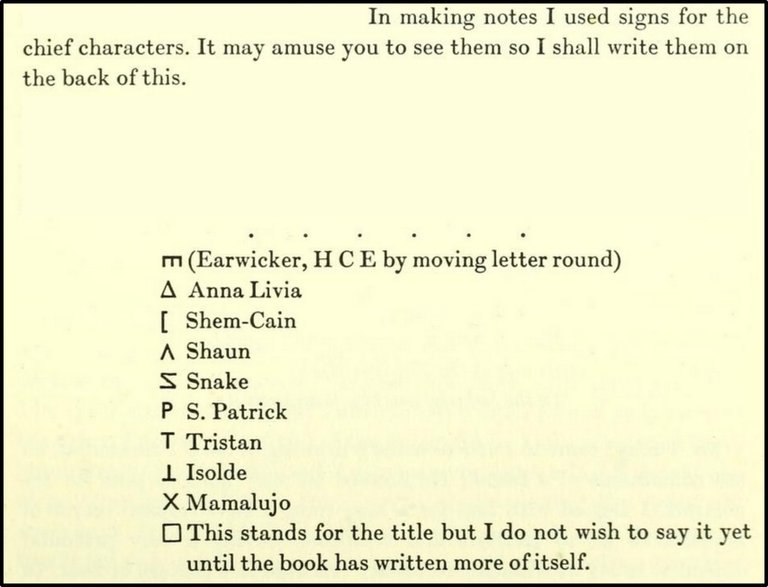

After our trip to the movie theatre we resume our judicial inquiry into the Battery at the Gate―the incident which dominates the closing ten pages of Chapter 3 of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. The following two paragraphs concern themselves with ALP’s letter and HCE’s coffin respectively. This concurrence of two apparently unrelated objects is an excellent example of what Roland McHugh calls the sigla approach to Finnegans Wake:

The distinguishing feature of my approach to FW is my concern with Joyce’s sigla. These marks appear in the author’s manuscripts and letters as abbreviations for certain characters or conceptual patterns underlying the book’s fabric ... I consider the adoption of sigla concepts to be fundamental to the correct appreciation of FW. ―McHugh, The Sigla of Finnegans Wake 3 ... 135

McHugh first tried to read Finnegans Wake in 1964, but he did not get very far:

Opening the book, I read slowly and mechanically as far as page 18, where I reached the lines ‛(Stoop) ... to this claybook ... Can you rede (since We and Thou had it out already) its world?’ I closed it. I felt that I had made a respectable attempt and that I could not read its world. ―McHugh, The Finnegans Wake Experience 25

This sentence comes immediately after the Mutt & Jute Dialogue. McHugh was thrown by the sudden tangential shift from a conversation about a Viking’s grave to a discussion of a piece of writing. This was just one of many such discontinuities, where the narrative seemed to jump haphazardly from one subject to another, unrelated one.

In the summer of 1965 McHugh returned to Joyce’s literary monster and began again with a renewed determination to finish it. Although the going was just as tough as before, he was beginning to discern, bit by bit, what Joyce was about in Finnegans Wake:

For instance, the original point on FW 18 where I had stopped the previous year coincides with a sudden change of context (which partly caused my stopping). Before this point, we have read a dialogue between ‛Mutt’ and ‛Jute’ about a burial mound ... It ends as follows:

Mutt. ―Ore you astoneaged, jute you?

Jute. ―Oye am thonthorstrok, thing mud.The words ‛thing mud’ suggesting the Thingmote, the Viking assembly in ancient Dublin, which took place on a kind of conical mound. The next sentence is the one I quoted earlier, exhorting the reader to stoop to the ‛claybook’, and leads to a two-page account of the origins of the alphabet and of printing. I can now explain the transition by observing that the text adheres faithfully to its real subject, the container siglum □, but I had no conception of such things at this stage. ―McHugh, The Finnegans Wake Experience 30–31

The two paragraphs we are now studying are in some sense foreshadowed by the passage in Chapter 1 that proved a stumbling block to McHugh. The first is unashamedly about a letter and its delivery by a postman. The second is just as unashamedly about a coffin. But if we adopt McHugh’s sigla approach to the exegesis of Finnegans Wake, we will immediately see that both are concerned with □, the square siglum. Joyce first explained that this siglum stands for the title [of the book, which was still a secret], but McHugh demonstrated that it actually represents any container of HCE―including Finnegans Wake itself (McHugh 1976:115). It is the whole book rather than just the title. But it is much more than this. It represents any receptacle of HCE, literal or figurative:

ALP’s letter is about HCE. He is the subject and the object of the Letter. Therefore, it contains HCE in a figurative sense.

The coffin in which HCE will shortly be buried is a literal container of HCE.

In the dream world of Finnegans Wake ALP’s letter and HCE’s coffin are identical and are represented by the same siglum. There is, then, no tangential change of subject. In the context of the judicial inquiry into the HCE affair the Letter might be identified with the transcript of the case.

First-Draft Version

When Joyce first drafted the episode known as the Battery at the Gate, there was no mention of ALP’s letter. Instead, the text passed directly from So in the present case which bears all the earmarks of a plot (see RFW 053.01) to a description of the coffin. Joyce actually began to describe This fender, but immediately amended this to This coffin, mistaken for a fender. It was only with the second draft that the letter was introduced. The following conflates this first mention of the letter with the first draft of the coffin paragraph. Note how abrupt the transition is from the letter to the coffin:

Next morning postman handed him a letter superscribed to Humphy Pot and Gallows King. This coffin, mistaken for a fender, had been removed from hardware premises which supply funeral requisites of all descriptions. ―Hayman 73

The rest of this early draft bears little resemblance to the published version. Some of the details found their way into the following paragraph (To proceed ...), while others were dropped altogether:

(Here Caracciolo & Nelson). The conscientious guard in the other case swore that Laddy Cumine, the butcher in the blouse, after having delivered some carcasses went & kicked at the door and when challenged on his oath by the imputed, said simply:

―I am on my oath, you did, as I stressed before.

―You are deeply mistaken, sir, let me tell you, denied McPartland. ―Hayman 73

Francesco Caracciolo

One person who figured in some early drafts before being displaced was a little-known Italian, Francesco Caracciolo. The parenthetical (Here Caracciolo & Nelson) may have been Joyce’s way of reminding himself to include something here about this Neapolitan admiral and revolutionary, who was executed on Admiral Nelson’s orders.

Caracciolo entered the British Navy and fought for the Crown in the American Revolution. In 1793 he served at Toulon under Nelson. In 1795 he participated in the Battle of Genoa under Lord Hotham. In January 1799 he returned to Naples and became involved in the establishment of the short-lived Parthenopean Republic. The British, led by Rear-Admiral Nelson, supported the counter-revolutionaries and blockaded Naples. In June Caracciolo fell into the hands of his former allies, who tried him for high treason. He was found guilty and sentenced to death. When informed of the sentence, Nelson ordered that he be hanged at the yard-arm of the Minerva―a vessel Caracciolo had assaulted during the revolution―and that his body be thrown into the sea. He was denied the customary twenty-four hours respite for confession, and his request to be shot instead of hanged was refused. The following morning the sentence was carried out as decreed.

In the end Joyce decided not to mention Caracciolo’s tragedy in Finnegans Wake. Nelson does crop up a few times, but never his Neapolitan Campaign. Caracciolo’s final appearance is in the fair copy of this passage that Joyce prepared in November 1923:

Whether or not, next morning the postman handed in a letter superscribed to Humpty, pot and gallows King. The coffin Nelson & Caracciolo, at first sight mistaken for a fender, had been removed from hardware premises, a noted house of the middle east which, as an ordinary everyday transaction, supplies funeral requisites of every description.

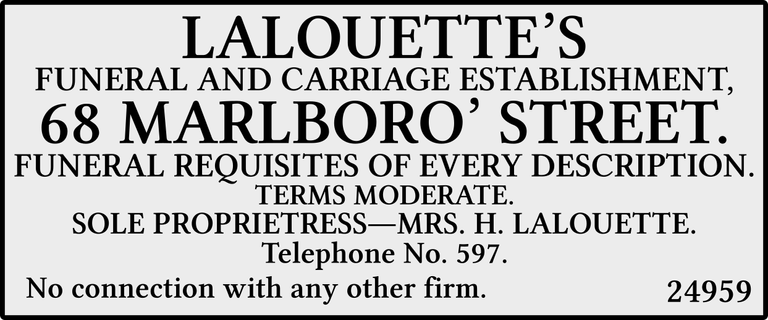

With the next draft this passage begins to closely resemble the final version. Nelson & Caracciolo disappear for good, to be replaced by the coffinmakers Oetzmann and Nephew. Oetzmann & Company manufactured furniture in Dublin and London between 1848 and 1947. The phrase funeral requisites of every description was borrowed from an advertisement for Lalouette’s Carriage and Funeral Establishment on Marlborough Street, Dublin (Annotations 66). Lalouette’s had been briefly mentioned in the opening episode of Ulysses.

Pot and Gallows King

In these early drafts HCE is referred to as Humphy Pot and Gallows King, later emended to Humpty, pot and gallows King. This draws upon an entry in one of the Finnegans Wake notebooks:

pot & gallows king ―VI.B.11.91c

Like Caracciolo, the pot and gallows king eventually disappears for good. But what was Joyce’s source for this entry, and who was the pot & gallows king? Googling the phrase pot and gallows turned up the following from an online dictionary of Scots:

Pot ... 7. A deep hole dug in the ground, a pit, now only hist. in phr. pot and gallows, for which see pit and gallows ...

Pit ... I. n. 1 (1) pit and gallows, a translation of the Latin feudal term furca et fossa, used to indicate the capital jurisdiction attached to a barony, by which the baron could put to death criminals found within his lands ... Hist. The word pit is gen. taken to refer to the water-filled trench in which females were executed by drowning. Others take pit as in sense 3. [An underground prison, a dungeon] but the evidence points to the practice as a survival from Anglo-Saxon and Teutonic law, whereby male malefactors were hanged and females drowned ... These powers had in practice much decayed in the 17th c. and were formally abolished in the Heritable Jurisdictions Act of 1746. ―Dictionary of the Scots Language

Some sources claim that the Scottish King Malcolm III Canmore introduced the drowning pit for the execution of women in 1057. This is the Malcolm who appears in Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the son of Duncan II. Was he Joyce’s pot & gallows king? The final version does refer to Letters Scotch, Limited and Edenberry. And washerwife [wisherwife] is Scots for washerwoman, though McHugh’s Annotations also gloss this as Old High German: Wunschweib, woman summonable by lover’s wishes.

Caracciolo was hanged from a yard-arm―a makeshift gallows. Henri IV of France once famously promised his subjects a chicken in every pot:

Si Dieu me donne encore de la vie je ferai qu’il n’y aura point de laboureur en mon Royaume qui n’ait moyen d’avoir une poule dans son pot.

If God grant me life, I will see that every laboring man in my kingdom shall have his chicken to put in the pot.

As quoted by Hardouin de Péréfixe de Beaumont in Histoire du roy Henry le Grand (1661). ―Wikiquote

Joyce puns on gallows and Latin: gallus, cock on more than one occasion. A criminal who deserves hanging is called a gallowsbird. But whether any of this is relevant is anyone’s guess.

transition

In June 1927 an early draft of this chapter was published in the third number of Eugene Jolas’ literary journal transition. These two paragraphs were printed together as a single continuous paragraph:

But resuming inquiries. Will it ever be next morning the postal unionist’s (officially called carrier’s, Letters Scotch, Limited) strange fate (Fierceendgiddyrich he’s hight, d. e., the losel that hucks around missivemaids’ gummibacks) to hand in an envelope, written in divers stages of ink, superscribed and subpencilled by yours A Laughable Party, with afterwite, to Hyde and Cheek, Edenberry, Dubbllenn, WC? Will whatever will be written in lappish language with inbursts of Maggyer always seem semposed, black looking white and white guarding black, in that siamixed twoatalk used twixt stern swift and jolly roger? Always and ever till Cox’s wife, twice Mrs Hahn, pokes her beak into the matter with Owen K. after her, to see whawa smutter after, will this kiribis pouch filled with litterish fragments lurk dormant in the paunch of that halpbrother of a herm, a pillarbox? The coffin, a triumph of the illusionist’s art, at first blench naturally taken for a handharp (it is hardwarp to tristinguish jubabe from jabule or either from tubote when all three have just been invened), had been removed from the hardware premises of Oetzmann and Nephew, a noted house of the gonemost west, which in the natural course of all things continues to supply funeral requisites of every needed description. Why needed, though? Indeed needed because the flash brides or bride in their lily boleros one games with at the Nivynubies’ finery ball and your upright grooms that always come right up with you (and by jingo when they do!) what else in this mortal world, now ours, when meet there night, mid their nackt, me there naket, made their nought the hour strikes, would bring them rightcameback in the flesh, thumbs down, to their orses and their hashes. ―Jolas & Paul 44–45

Only a handful of further details were added between 1927 and 1939, when the first edition of Finnegans Wake was published.

Some Interesting Details

To conclude, let us take a closer look at a few of this section’s outstanding puzzles.

- Fierceendgiddyrex Vercingetorix, the leader of the Gauls who was defeated by Julius Caesar at the Battle of Alesia in 52 BCE. But why is the postman―ie Shaun the Post―identified with Vercingetorix? In one of the Finnegans Wake notebooks we read the following enigmatic note:

Vercingetorix = Man who / takes round funeral letters ―VI.B.11.5k

Vercingetorix did indeed come to a Fierce end―he was executed during Caesar’s first triumph in 46 BCE: The coffin, a triumph ... ?

The first edition’s Fierceendgiddyex has been emended to Fierceendgiddyrex by Rose & O’Hanlon.

S.A.G. Saint Anthony Guide, written on envelopes by pious Catholics to ensure the delivery of their letters. St Anthony of Padua is the patron saint of lost articles. See RFW 317.37, where the full phrase is given, in association with another Anthony, Trollope, the novelist who was employed by the Irish postal service for almost two decades. Trollope is generally credited with introducing the pillarbox to Britain and Ireland.

stern swift The two Irish-born writers Laurence Sterne and Jonathan Swift are often juxtaposed in Finnegans Wake―representing Shem & Shaun. It is also a happy coincidence that Swift’s immediate predecessor as Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral was a John Sterne.

jolly roger ... Cox’s wife Roger Cox was Jonathan Swift’s parish clerk at Laracor, County Meath. He is described as being of a lively jovial temper in C H Wilson’s Swiftiana of 1808 (Wilson 4). The Jolly Roger is the pirate flag of a white skull & crossbones on a black field―black looking white and white guarding black.

Will it bright upon us, nightle, and we plunging to our plight? Well, it might now, mircle, so it light. The refrain of Percy French’s popular song Are Ye Right There, Michael?

Are ye right there, Michael, are ye right?

Do you think that we’ll be there before the night?

Ye’ve been so long in startin’

That ye couldn’t say for sartain

Still ye might now, Michael,

So ye might!

The song was written at the expense of the West Clare Railway, which was notorious for its unpunctuality.

twice Mrs Hahn Ida, Countess von Hahn-Hahn. The 19th-century German novelist was born von Hahn, and married her cousin, who was also a von Hahn, to become von Hahn-Hahn, a name she kept even after their divorce.

Owen K. Irish: Eoghan, Owen, Eoin. This Celtic name is often used to translate the name John, so Owen in Finnegans Wake represents Shaun. Shaun is also called Kevin (to Shem’s Jerry). Hence Owen K. There is also an Owenkeagh River in County Cork―Irish: Abhainn Caoch, Blind River. See O’Hehir, A Gaelic Lexicon for Finnegans Wake 357, 406–407.

There was also an undertaker in Dublin called Owen Kerrigan (Glasheen 220, who credits Richard Ellmann with the discovery). In Ulysses the fictional Corny Kelleher is the manager of a real funeral establishment, H J O’Neill’s, 164 North Strand Road. In 1904 the actual manager of the firm was an S. Kerrigan (Thom’s Dublin Directory 1904:1559). Simon Kerrigan (1855–1936), it has been suggested―by Vivien Igoe, curator of the James Joyce Museum at Sandycove―was Joyce’s model for Kelleher (John Hunt, The Joyce Project).

In I.5, The Mamafesta, when the hen discovers the remains of ALP’s letter in the kitchen midden behind the Mullingar House, she is being watched by Kevin (RFW 088.01 ff).

kiribis pouch Japanese: kiribi [切火], flint sparks. A kiribi pouch, or chuckmuck, was a leather pouch containing a flintstone, which was used in a purification ritual of the same name to ward off evil spirits―for example, when embarking on a voyage or a new endeavour―by striking sparks from it. In Ancient Egypt the ibis bird was sacred to Thoth, the god of writing. Also Estonian: kiri, letter (message), writing.

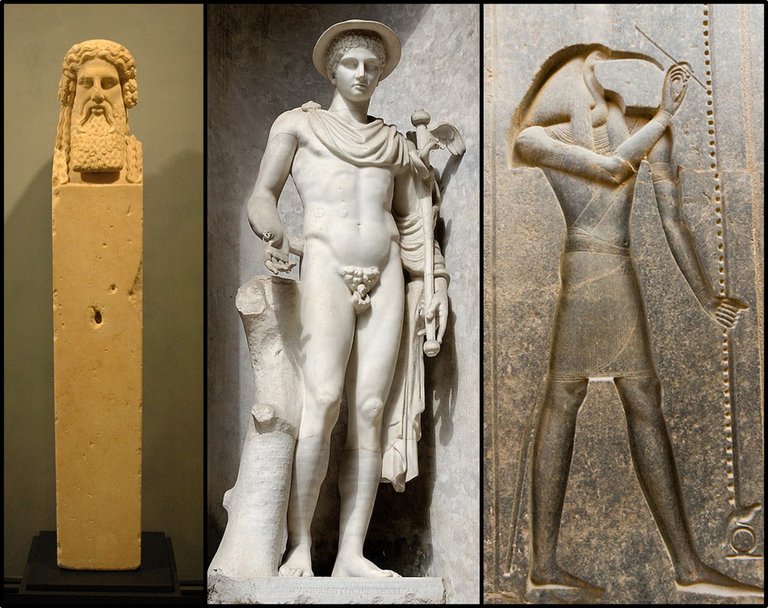

herm A herm or herma was a body-size quadrangular pillar surmounted by a head, usually of the god Hermes, found in ancient Greece. They were used as pillars, sign-posts, mile-stones, boundary marks, etc. As the Greek equivalent of the Egyptian Thoth―the ibis-headed god―Hermes was the god of writing.

a triumph of the illusionist’s art The opening chapter of Finnegans Wake mentioned that provost scoffing (RFW 005.04), which alludes to the legend of the Prophet Muhammad’s coffin levitating. That was a foreshadowing of this moment, in which the levitation is scoffed at, being a mere illusionist’s trick rather than a genuine miracle.

rattanfowl ... oscar Two more borrowings from W H Downing’s Digger Dialects: A Collection of Slang Phrases used by the Australian Soldiers on Active Service:

- rat-and-fowl Australian shilling. Also German: rattenkahl, bald as a rat, completely bare. The word is included in the Deutsches Wörterbuch of the Brothers Grimm, where it is glossed as ganz und gar [completely], mit stumpf und stiel [root and branch].

- oscar money (rhyming slang for cash after the Australian actor Oscar Asche).

Fairy Tales

In Finnegans Wake: A Plot Summary John Gordon writes:

The coffin is apparently, as in I/4 [RFW 061.02], made of glass, reminiscent of the glass coffin in which Snow White sleeps until awakened with a kiss. ―Gordon 134

Snow White is one of the Grimms’ Fairy Tales, but the closing lines of this passage―which echo RFW 009.13–15―sound more reminiscent of Charles Perrault’s French tale of Cinderella:

Indeed needed ... because the flash brides or bride in their lily boleros one games with at the Nivynubies’ finery ball and your upright grooms that always come right up with you ... what else in this mortal world ... when meet there night ... the hour strikes, would bring them rightcameback in the flesh, thumbs down, to their orses and their hashes.

brides or bride Plural and singular because Issy is schizophrenic. St Bride refers to one of Issy’s avatars, Brigid, who was both Christian saint and pagan goddess.

bolero A short, buttonless jacket or blouse, open or tied in front and ending at the diaphragm.

German: Mitternacht, midnight.

In his online Finnegans Wake blog, Gordon adds:

66.35-67.6: “Indeed ... hashes:” gist: such funerary articles are necessary in order to remind high-flying youth of their mortality and bring them down to earth. The scenario is reminiscent of Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death.”

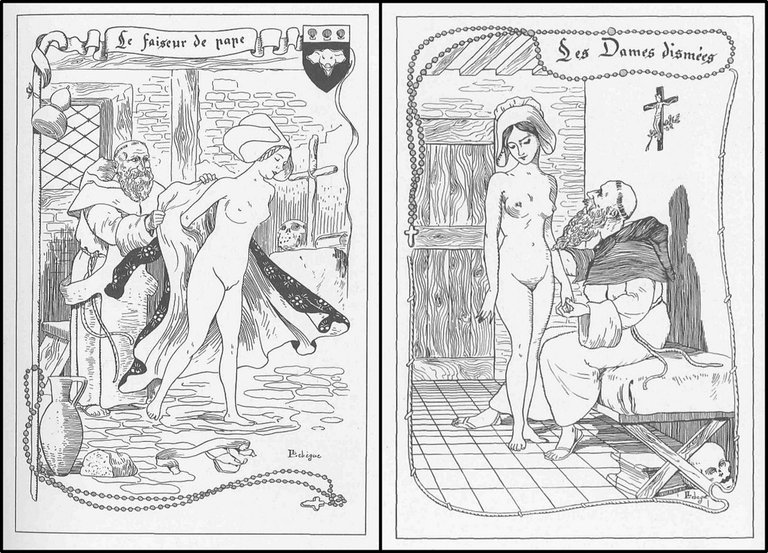

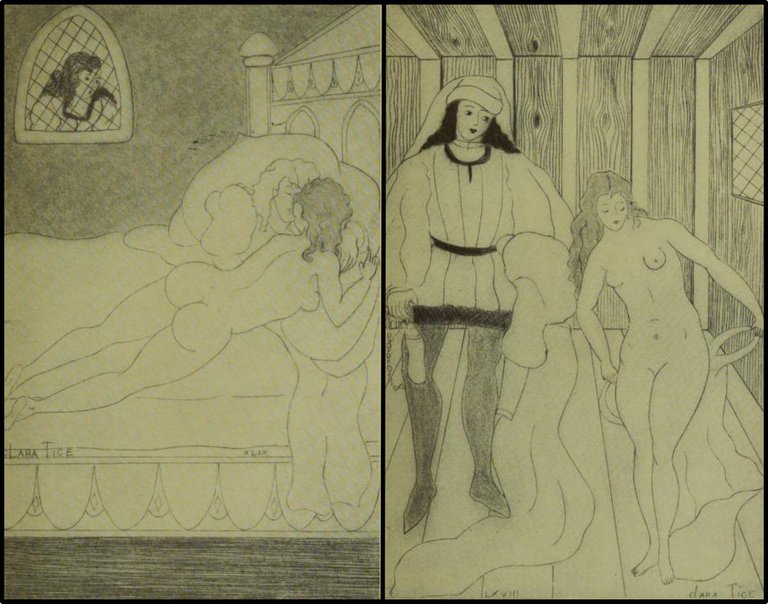

Some entries in one of the Finnegans Wake notebooks, however, suggests that Joyce was inspired by another collection of French tales: Robert B Douglas’s One Hundred Merrie and Delightsome Stories. This is an English translation of the French 15th-century classic Cent Nouvelles Nouvelles. Daniel Ferrer, who collated all of Joyce’s quotations from this work in 2015, cited the 1899 edition, which has Léon Lebèque’s sexually explicit illustrations. Danis Rose & John O’Hanlon, however, cite Andrew Machen’s 1923 edition, which is illustrated with bawdy images by Clara Tice:

It is not clear why Joyce took up this collection of bawdy short stories in its English version. According to George Saintsbury, quoted in the Introduction, it is “undoubtedly the first work of literary prose in French”. The stories published in 1452, are supposed to be written by different members of the court of the Duke of Burgundy, but they are by a single hand, probably not Antoine de la Salle, and certainly not the future king Louis XI, as it was believed for a long time. Joyce seems to have read desultorily, jumping back and forth from one story to another, but he took a substantial number of notes, often relating the material of the stories to Tristan and Isolde. ―Ferrer 60–61

- your upright grooms that always come right up with you This draws on a note Joyce made from Stories 52, The Three Reminders, and 53, The Muddled Marriages:

came up with / upright ―VI.B.17.052k

Story 52 One day after that, he, being fond of amusement, was in the fields, and his dogs put up a hare. He spurred his horse after them, and came up with them in a valley, when his horse, which was galloping fast, slipped, and broke its neck.

Story 53 One morning there were assembled in the cathedral of Sainte Gudule at Brussels, many men and women who wished to be married at the first Mass, which is said between four and five o'clock; and amongst others who wished to enter this sweet and happy condition, and promise before the priest to live honestly and uprightly, were a young man and a young woman who were not rich, who were standing near each other, waiting for the priest to call them to marry them. ―Douglas 2:30

Pace Ferrer, the note on upright might have been taken from Story 67, The Woman with Three Husbands. All three stories involve grooms:

About three years ago a noteworthy adventure happened to one of the fur hats of the Parliament of Paris. [Editorial Footnote: The councillors of Parliament wore a cap of fur, bordered with ermine.] And that it should not be forgotten, I relate this story, not that I hold all the “fur caps” to be good and upright men; but because there was not a little, but a large measure of duplicity about this particular one, which is a strange and peculiar thing as every one knows. ―Douglas 2:102

Why did these particular phrases―all of them quite trite and commonplace―catch Joyce’s fancy? Your guess is as good as mine.

The first quotation from Douglas’s One Hundred Merrie and Delightsome Stories is the phrase our eyes demand their turn (RFW 042.21–22). There are only about fifteen or so allusions to the collection in all. FWEET lists fifteen, but omits the one in the coffin paragraph. The Finnegans Wake notebooks contain about eighty quotations from Douglas’s translation, most of which were never used.

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York (1944)

- Robert B Douglas (translator), One Hundred Merrie and Delightsome Stories, Volumes 1–2, Léon Lebèque (illustrator), Charles Carrington, Paris (1899)

- Robert B Douglas (translator), One Hundred Merrie and Delightsome Stories, Volume 1, Volume 2, Andrew Machen (editor), Carbonnek (1924)

- Walter Hubert Downing, Digger Dialects: A Collection of Slang Phrases Used by the Australian Soldiers on Active Service, Lothian Book Publishing Co, Melbourne and Sydney (1919)

- Daniel Ferrer, VI.B.17: A Reconstruction and Some Sources, Genetic Joyce Studies, Issue 15, Centre for Manuscript Genetics, University of Antwerp, Antwerp (2015)

- Stuart Gilbert & Richard Ellmann (editors), The Letters of James Joyce, Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3, Viking Press, New York (1957, 1966)

- Adaline Glasheen, Third Census of Finnegans Wake, University of California Press, Berkeley, California (1977)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1963)

- Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul (editors), transition, Number 3, Shakespeare & Co, Paris (1927)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce, James Joyce: The Complete Works, Pynch (editor), Online (2013)

- Ian MacArthur & Viviana-Mirela Braslasu, A Second Finnegans Wake Miscellany, Genetic Joyce Studies, Issue 22, Centre for Manuscript Genetics, University of Antwerp, Antwerp (2022)

- Roland McHugh, The Sigla of Finnegans Wake, Edward Arnold, London (1976)

- Roland McHugh, The Finnegans Wake Experience, University of California Press, Berkeley, California (1981)

- Roland McHugh, Annotations to Finnegans Wake, Third Edition, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland (2006)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

- Charles Henry Wilson, Swiftiana, Volume 1, Richard Phillips, London (1804)

Image Credits

- Pillar Box: Pillar Box from the Reign of George V, Annesley Bridge, Dublin, © Patrick Comerford, Creative Commons License

- That Prophet’s Coffin: An Engraving of Muhammad’s Coffin Levitating, Broer Jansz, The History of the Origin, Family, Birth, Education and Teachings of the Great False Prophet Mohammed, Amsterdam (1640), Public Domain

- Crossed Letter: A Page from a Crossed Letter by an Irish Emigrant in America (1839), Public Domain

- Roland McHugh: © Roland McHugh, Fair Use

- Francesco Caracciolo (left): Anonymous Portrait, Public Domain

- Francesco Caracciolo (right): Francesco De Gregorio (artist), Palazzo San Giacomo, Naples, Public Domain

- The Slaughters of Altamura: Michele Cammarano (artist), Museo Nazionale di San Martino & Certosa, Naples, U Marzani (photographer), Bridgeman Images, Public Domain

- Advertisement for Lalouette’s: Business Card, Public Domain

- Malcolm III Canmore of Scotland (left): Malcolm III & Queen Margaret, Seton Armorial (1591), National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, Public Domain

- Malcolm III Canmore of Scotland (right): Jacob Jacobsz de Wet II (artist), Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, Public Domain

- A Scottish Drowning Pit: Gallow Hill, Mugdock Country Park, Milngavie, © Rosser1954 (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Eugene Jolas: Anonymous Photograph, Public Domain

- Elliot Paul: Luis Quintanilla (photographer), © The Estate of Luis Quintanilla, Fair Use

- Giant Statues of Caesar, Vercingetorix & Archimedes at Le Palais Idéal, Designed by French Postman Ferdinand Cheval: Facteur Ferdinand Cheval, Le Palais Idéal, Hauterives, France, © Eric Bajart (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Slieve Callan, West Clare Railway Locomotive: Ennis Railway Station, © Tim Abbott (photographer), Creative Commons License

- A Herm: A Herm of Hermes, Roman Copy of the Hermes Propyleia by Alcamenes (50–100 CE), Getty Villa, Los Angeles, Marshall Astor (photographer), Public Domain

- Hermes: Hermes Ingenui, Roman Copy of Greek original (2nd Century BCE), Vatican Museums, Marie-Lan Nguyen (photographer), Public Domain

- Thoth: Relief of Thoth Carved on the Back of the Throne of the Seated Statue of Ramses II, Luxor Temple, Egypt, © Alfred Molon (photographer), Fair Use

Useful Resources

- FWEET

- Joyce Tools―Includes Thom’s Dublin Directory for 1904

- Jorn Barger: Robotwisdom

- The James Joyce Scholars’ Collection

- FinnegansWiki

- James Joyce Digital Archive