The grey whales go by

now dying of starvation -

when will we wake up?

I had a most disturbing story come across my feed this morning, of my beloved California grey whales, with four of them having washed ashore dead in the San Francisco Bay area, in the short span of eight days.

Similarly, three washed ashore dead in the same area last year, and in all cases, the whales were emaciated, and literally starving to death, primarily because of human pollution, blunt force from being hit by ships, overfishing, and a lack of will among those lawmakers in our government to actually do anything to address the worsening issue.

And it isn't just grey whales,

The Southern Resident orcas, which are a once-vibrant group of matriarchal pods of coastal, fish-eating "killer whales," living in the Puget Sound area of Washington State, are also steadily losing ground, as the Coho salmon they have depended upon for millennia have been all but fished out of existence for human consumption.

I majored in marine biology in college, largely because although I love all animals, I've had a special affinity for marine life since I was a young child.

I've written elsewhere about my earliest encounter with whales that I recall, when I was around five years of age, and accompanied my parents for an afternoon visit with close friends of theirs who lived in the terraced hills of the Palos Verdes peninsula, high above and overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

We were all sitting in their back yard, enjoying the lovely sunny weather, and as the adults were conversing among themselves, I was befriending their huge (to me) white standard poodle, whose name was King Tut. And as I petted King Tut, I could see large black shapes in the water far below us, and I realized that, much to my surprise, the shapes were moving.

So I asked my mother what they were, and she told me, "Those are whales."

And I was transfixed, fascinated, and awed at the same time . . . I didn't know just how far we were from the water, but even at that age I knew it would be a long walk, and that if we could see the whales that clearly from such a distance, they must be really huge.

And my love affair with whales was born.

But whales weren't the only marine creatures off our coast that I loved.

I was a huge fan of the nature programming from National Geographic and Jacques Cousteau, my family watched them whenever they came on, and I already wanted to be a SCUBA diver (which didn't thrill either of my parents), and to spend weeks if not months at sea doing the kind of research and documentation that we saw in the specials.

And then came "Blue Water White Death," the 1971 documentary produced by Peter Gimbel and James Lipscomb about their attempts to film the great white shark in its natural element for the first time; and its remarkable companion volume, "Blue Meridian," written by Peter Matthiessen, who accompanied them on the voyage.

I had actually forgotten that Tom Chapin had accompanied them on the voyage as well; he was the folk singer brother of the great Harry Chapin, which is interesting, because I always loved them both, and I'm amazed that I failed to remember his part in the film.

Then again, it HAS been fifty years since its release, and I haven't seen the film since the mid- to late-1970s. C'est la vie.

But I absolutely remembered Ron and Valerie Taylor, the Australian spearfishing champions who were to provide some of the most amazing undersea cinematography of the film, as well as the legendary Stan Waterman, an amazing and accomplished undersea cinematographer in his own right.

The sheer talent of those who undertook the voyage was astounding, and what they accomplished together was an unprecedented exploration of the great white shark, in a way in which it had never been seen before.

Gimbel and his crew were even accompanied by Australian spearfishing champion Rodney Fox, one of the few men who had survived a full on attack by a great white shark, and had the massive scars to prove it.

I have run across some comments on the Internet, however, that I'd like to refute: at least one commenter blasted the film crew for "mercilessly killing whales," which quite simply never happened.

When they arrived at their first destination, off the coast of Durban, South Africa, an area that coincidentally in the mid-1970s had among the highest numbers of attacks on humans by great white sharks, they followed a whaling boat, from which they'd obtained permission from the captain to place their shark cages next to the dead whales, in order to film the sharks feeding on the whale carcasses.

NO member of the film crew ever killed a single whale.

The whaling ship was going to be hunting and killing sperm whales whether or not the film crew ever showed up. But show up they did, and in the process, they showed American and international audiences, really for the first time, the utter brutality that is commercial whaling.

The whaling scenes are hard to watch, including showing a sperm whale being harpooned from the whaler's perspective, followed by the suffering whale bleeding out on camera, which created enough anti-whaling sentiment that the following year, in 1972, US President Richard M. Nixon signed into law the Marine Mammal Protection Act, permanently protecting whales from being hunted and killed in American waters.

And a number of other whaling moratoriums were passed in other countries, over the next few years, including in Australia.

Not surprisingly, the film and its companion book would influence many people all over the world, including myself, as the book was my final push to ultimately major in ichthyology, and to specialize in the study of sharks, skates and rays.

But the most famous example of its influence was on Peter Benchley, who four years after the film's release would release his smash hit novel, "Jaws," in which he modeled the character of wealthy ichthyologist Matt Hooper, played by Richard Dreyfuss in the film made from the book, on wealthy filmmaker Peter Gimbel.

In addition to the book and film, Benchley was inspired by a well known series of shark attacks that took place in Matawan Bay, and deeply into nearby Matawan Creek, in Matawan, New Jersey, in July 1916.

Over a twelve day period, the shark killed four people and severely mauled a fifth, and was ultimately caught and killed in nearby Raritan Bay. When dissected, the shark contained roughly fifteen pounds of human remains, which left no doubt that they had caught the right shark.

Although in the 1970s it was still being officially reported as an immature great white shark, I knew that was extremely unlikely, as white sharks are known to avoid, and not enter fresh, or even brackish water.

The record has since been corrected, and the culprit is now identified as a bull shark, which is the only species of shark known to inhabit both fresh and saltwater, and in fact becomes more aggressive in fresh water.

When Steven Spielberg began preparing for the filming of "Jaws," he contacted Gimbel to work for him, but Gimbel reportedly declined, stating that he was a filmmaker, not a cameraman.

But Ron and Valerie Taylor, who provided some of the most amazing underwater sequences for "Blue Water White Death," did go to work with Spielberg, and recreated one of the most pivotal scenes from "Blue Water White Death," where a large white shark got its fin stuck in the shark cage, and bent the bars of the aluminum cage in its struggles to break free.

"Blue Water White Death," much like its successor "Jaws," is not a film that could be made today, or at least not in the same way. For one thing, only in the late 60s (the actual voyage took place in 1969) would a documentary film crew have a folk singer in residence, although I personally believe it was a masterstroke.

But then, I'm a late blooming flower child.

For another, in some of the sequences from the open ocean, where they were again filming sharks feeding on whale carcasses, although no great whites were in evidence, they had a surfeit of oceanic white tip sharks, then the most prevalent pelagic species of shark.

At one point, they left their shark cages amidst at least hundreds, if not thousands of oceanic white tip sharks and as they left the safety of the shark cages to swim among the feeding sharks, you can hear one of the filmmakers saying, "There were too many to count. There were thousands of them."

Today, fifty years later, the vast schools of oceanic white tips are no more, as they have been hunted to near extinction, especially by the despicable shark finning operations, and they are now only rarely seen.

Much as in my native Southern California, whereas blue sharks used to be our constant companions during dives and sailing trips, which followed our boats part my out of a desire for us to throw something tasty overboard, but mostly out of natural curiosity, now they are seen only sporadically, and never in great numbers, but usually solitary, or more rarely in pairs.

Sharks are NOT the mindless killing machines as depicted in "Jaws," and as Peter Benchley discovered, once he realized that sharks were being killed in vast and unsustainable numbers as a direct result of his book and the subsequent film, he learned that sharks are deserving of our love and protection.

Sharks are a LOT smarter than we've ever given them credit for. Sharks, given the opportunity, display a capacity for play, which is generally considered to be a marker for higher intelligence.

You don't stick around, relatively unchanged, for 300 million plus years and more, by being stupid. Sharks are amazingly well adapted to their habitats, but we humans are changing the oceans faster than they can adapt, which often has tragic consequences.

Benchley, much to his credit, spent the last several decades of his life trying to undo the damage that his book and film had done, and to educate people regarding the true worth of sharks, and why they are so very vital for us to keep around, as protectors of our oceanic ecosystems.

Interestingly, while writing this, a headline came across my feed regarding a British man who had survived 117 days (or 118, depending upon the source), aboard a raft with his wife, after a whale stove in their boat and set them adrift in the open ocean.

The gentleman in question had died in 2019, so I'm not certain why it was being reported as recent news, but that's the internet in a nutshell.

But my mind immediately went to another book I'd read in the 1970s, "Survive the Savage Sea," about Scottish sailor Dougal Robertson, whose 43 foot schooner was stove in by a large orca, from a pod that had surrounded the boat, which began with his sudden realization that he, his wife, their three sons, and their young guest had roughly two minutes to get to the life raft, before the boat sank and carried them to their deaths.

Their story of survival on the open ocean has always stayed with me, and if you are in the mood for an excellent true tale of survival against the odds, I highly recommend it.

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-stoke-staffordshire-18877090

But, as it happens, the couples' tale is every bit as harrowing, and moving, as they were lost at see for over three times as long, with just the two of the, with twenty days worth of water, and they came to view the animals they interacted with as friends and neighbors.

I'd love to learn more of their tale.

https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/brit-who-survived-117-days-21014862

In any case, in an effort not to depress myself further, I opted instead to make a playlist of some of my favorite instrumental music, in order to keep myself somewhat sane.

This is a fairly laid back mix, mostly smooth jazz, jazz fusion, some progressive rock and experimental stuff, mostly instrumental, that are pieces that have kept me sane for several decades and more. I hope that you enjoy it.

Music is natural medicine in its purest and least adulterated form. ;-)

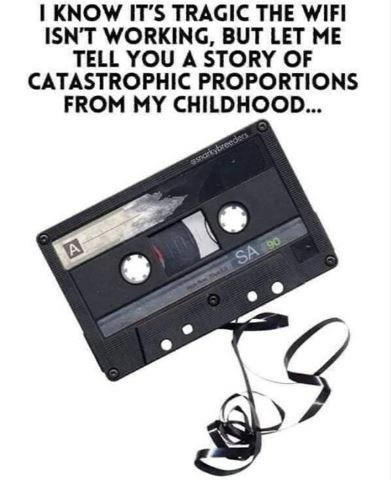

And then of course, there is humor, also a completely legit form of natural medicine, such as this gem, sent to me by my husband earlier today:

To everyone who has spent at least some of your time trying to prevent the destruction of wildlife and their habitats; thank you.

To those who still think that the only good shark is a dead shark, you are mistaken, and I implore you to look into it further, as you might just find yourself on an unexpectedly fascinating journey.

Life is wonderful, and is getting better, better, and better.

That's my story, and I'm sticking to it.

This is my third haiku post in just over three days, which I'm patterning after the original 30-day haiku challenge by @brokemancode, on Steemit when I first joined the platform, and I intend to keep it going for at least thirty day, and likely even longer.

Thanks for hanging in there with me.

#earthtribe #tribevibes #naturalmedicine #tribegloballove #poetsunited #isleofwrite #tarc #yah #ecotrain #smg #ghsc #spunkeemonkee #thirtydayhaikuchallenge #teamgood #steemsugars #teamgirlpowa #womenofsteemit #steemusa #qurator #music #rock #steemitbasicincome #bethechange #chooselove #photography #beauty #love #culture #peacemaking #peacemaker #friendship, #warmth #self-respect #respect #allowing #animals #community #unity #love #loss #mourning

CommunityIIDiscord

CommunityIIDiscord