Part 2: What is a Conceptual Question?

Introduction – Meanings and Concepts

How do we make sense of the world out there? How do we know anything? How do we discern between different things so that it makes sense? Think about the following utterance a speaker can make:

“I am hungry. I need food”.

For us to understand and make sense of this, we need to have concepts of “hunger”, “food”, and “I”. We also need to be able to distinguish between these concepts. This leads us to a new type of question: Conceptual questions.

In the previous essay, I stated that we can have philosophical questions. A conceptual question is one type of philosophical question we can ask and explore. However, what are concepts? And what are their relation to meaning? Look at out example utterance again, what does the words “hunger”, “food”, and “I” mean? Understanding the meaning of a word, in a sense, entails that we understand the concept. Concepts also help us give meaning to things and words. However, meanings are not concepts, and vice versa. We can thus differentiate between meanings and concepts. Meanings, we might say, are in the mind, while concepts, we might say, are in the world. Let me explain.

Connotation and Denotation

We can introduce two new words into our framework: “connotation” and “denotation”. Denotation has to do with the range of meaning; in other words, it has to do with all things in the world out there which we could put under a concept. For example, the denotation of “dog” includes my “puppy Jack” and the “neighbour’s dog who does not stop barking”. All the things out there in the world that match the connotation of “dog” falls under the denotation of the concept “dog”. Connotation is, thus, the characteristics of the concept or the meaning content of the concept. For example, the connotation of “dog” is that it has four legs, barks, and has a furry coat.

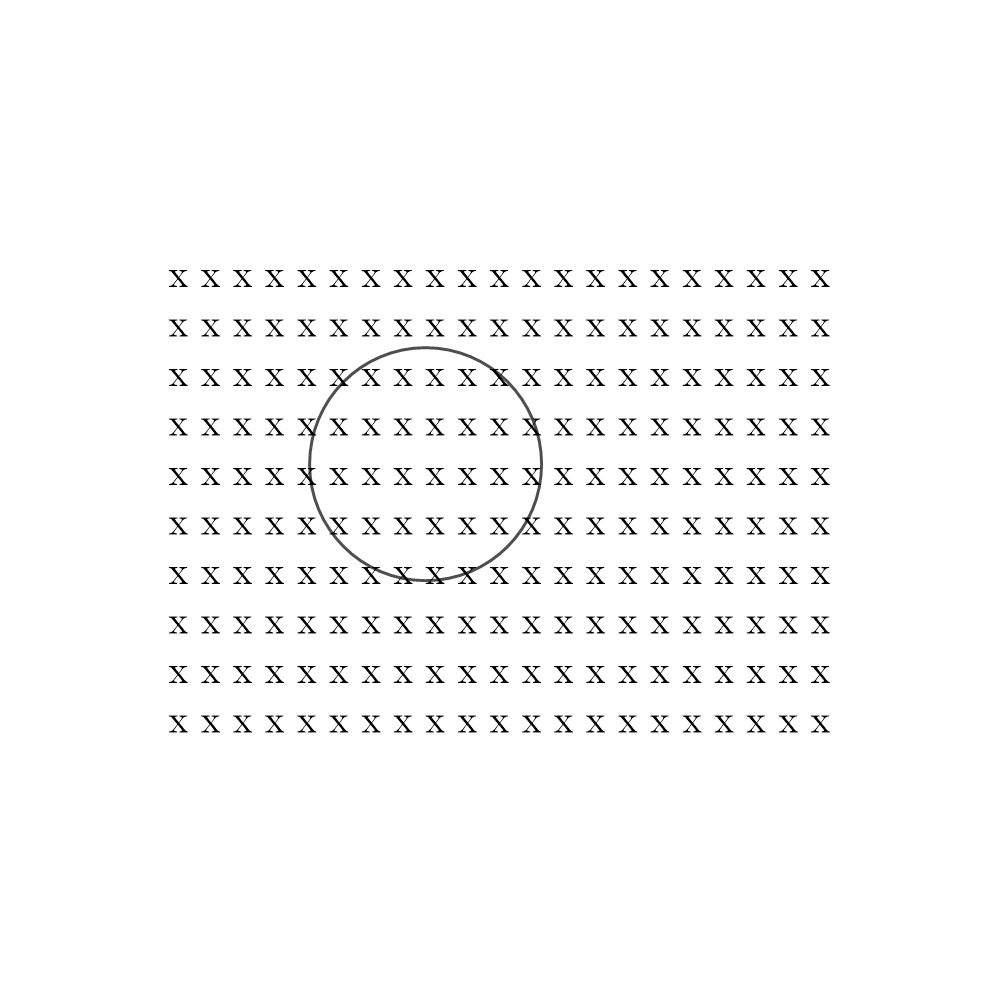

We can take this further. Denotation usually refers to the “extension” of a concept, in other words the existing or extending things in the world. Think about a net one throws into the world out there: everything in that net is what falls under out concept. But what is the parameters of our net we cast into the world? We do not want to catch everything our net lands on. Our parameters are the connotations which normally refers to the “intention” of a concept. We intend to catch certain things in the world; our net will thus only catch what we “intend”. Look at the following image which tries to illustrate this metaphor about the net:

The world out there is represented with the x’s; our net that we cast is the concept. We can note two things here:

(i) The concept, as represented in the image above, consists out of two things. The connotation or intention is represented by the circle. The denotation or extension is represented by the things which falls inside of the circle. Our concepts function like this. We cast the net which is our “intended meaning” and everything the net catches in the world is our “extended meaning”.

(ii) Note that some of the x’s in the above image does not fall perfectly inside of the circle. Some of them overlap, in other words, half is inside of the circle, half is outside of the circle. We can call these x’s “fuzzy concepts”. I will briefly talk about this at the end.

Rules About Drawing the Circle

So, how do we go about drawing this circle? There are some rules we need to follow to draw this circle. We cannot simply go about drawing the circle without these rules, otherwise we can get “weird concepts”. I will briefly highlight two rules, otherwise we might get concepts like a “square circle” or sentences like “the walk tastes creamy.”

(i) There are logically impossible concepts. We cannot have these concepts next to each other. The “square circle” is by far the most used example of this. Logically these concepts contradict each other. Consequently, the first rule is that we cannot have contradicting concepts, which has antithetical relationships, together.

(ii) There are what we might call “clashes of classes” concepts. There is no logical contradiction, rather it does not make conceptual sense to place these things in a certain relation; they form part of different classes even though they might both be, for example, nouns. The meaning of these sentences is, for a lack of better terms, weird. This might make poetic sense, but philosophically speaking they do not have coherent meaning. Take the sentence: “the walk tastes creamy”. We are not breaking any logical rules, there is a noun and a verb and an adjective. The sentence structure is the same as “the toast smells burnt”. However, a walk cannot “taste” like anything because our concept of “walk” does not allow for it to have that characteristic. It falls into another class of words. Consequently, the second rule is certain concepts belong to different classes, and these cannot be placed in relation to each other.

Conceptual Analysis and Conceptual Questions

Let us take stock and return to our “fuzzy” concepts. Firstly, when we cast our net in the world, there are some extensions or denotations which falls not wholly inside or wholly outside of the connotation or intention. This is, as said, fuzzy concepts. Secondly, there are sometimes concepts which get out of date or change their meaning. I discussed two of these rules. Now this is where we enter with conceptual questions or conceptual analysis.

When we struggle to find a word to express something or if a word gets some outmoded connotation or denotation, we can start to form our conceptual question which then leads to a conceptual analysis. These conceptual questions normally arise when we want to clarify a concept, or we are uncertain of the rules we use to express something. Normally, we do this to clarify a concept. But we cannot rely on empirical evidence for this. We might state that a conceptual analysis is pre-empirical. Normally, philosophy does not deal with empirical things, that is science’s domain. Take, for example, the concept of “happiness”. Yes, science can tell us about happiness to a certain extent, but is this not a concept which requires philosophical conceptual analysis? Happiness is not a wholly empirical concept. Take, for example, our main question in this series: “How might I live my life?”. Does happiness not play a crucial role in answering this question? If you agree that it does, can empirical data give us the answer to how I might live? Not necessarily, it might help but it cannot answer it totally.

How I Might Live as a Conceptual Question

“How I might live” is a conceptual question we struggle with in this series. Why do I say this? Because so many factors go in to answering this simple question. All these factors need to be conceptually analysed. Living life in an examined manner is not free from labour. However, even if this might seem like a laborious project, living an examined and philosophical life surely tops an unexamined and unconscious life.