Hi everyone, this is my first post in this community. This is part of a series I was doing but its current themes fit better here.

I have the following principles: my I-mind exists, I have a body, I am surrounded by things -surrounded by Existence, for I am not the only thing that exists-, deciding what to do with my mind and body is up to me, I have Descartes' three provisional moral rules (see here: https://peakd.com/hive-133872/@santiago-yocoy/una-moral-provisional-mientras-se-investiga-a-provisional-moral-while-investigating). To know what is the best thing to do I must find out not why there are things, but the nature, the essence, of what two of them are, my mind and my body. But, starting from nothing, I see no reason to believe that my mind and body must be fundamentally different from any other things. Therefore, I wonder what is the best method or ways to know about things in general.

If I went further than Descartes with one of the rules of his method, let us look at the merits of the other three just in case I can do the same. The second can be called thinking analytically, the third synthetically, and the fourth is to record as many things as possible.

There is an interrelation between these, which is that in analyzing - in breaking things down into as many parts as possible - I am discovering and recording more things than are offered at first sight, I am seeing what and how much there is; and with synthesis, I discover how the things I analytically separated were united, or how those I judge to be inseparable into smaller parts are related to each other. Of note is that the main thing here to perform the actions is my mind, with my body being no more than a facilitator in certain tasks of exploration.

Now, these principles do not in themselves tell me how to carry them out, nor what - given the finiteness of time and my energy - to prioritize. But I already have a priority, which is to understand my mind and body, and it turns out that among the things that exist are those that claim to be able to help me do so. I have already talked about religion (https://peakd.com/hive-133872/@santiago-yocoy/ensayo-pensamiento-cuerpo-y-dios-essay-thought-body-and-god), now it is time to talk about science; supposedly, according to many people, the best method to know.

In the first place, I could analyze more or less formal definitions of science. An elementary or high school textbook definition would say something along these lines: science is that activity that uses a specific method, consequently called scientific, which consists of observing a phenomenon, making a hypothesis (provisional explanation) about its nature, carrying out an experiment (doing a thing having said before that it will have such an effect on the phenomenon or by the phenomenon on the predictive side; or to know how it behaves before certain things (one substance with another), on the descriptive side) to test the hypothesis, and if the experiment works I have an isolated fact or a theory; a theory is a set of facts about reality with logical relationship between them that have been experimentally tested; and if the experiment does not meet the expectations, the hypothesis is discarded and another one is thought of or one tries to think what could have gone wrong in the experiment.

The method thus described would not contradict the few assumptions I have adopted so far; however, I see that the problems might lie in how to choose experiments correctly to know whether they prove what I want them to prove, how to know that there is no interference of some kind on the portion of Existence that I am trying to set aside from the others for analysis.

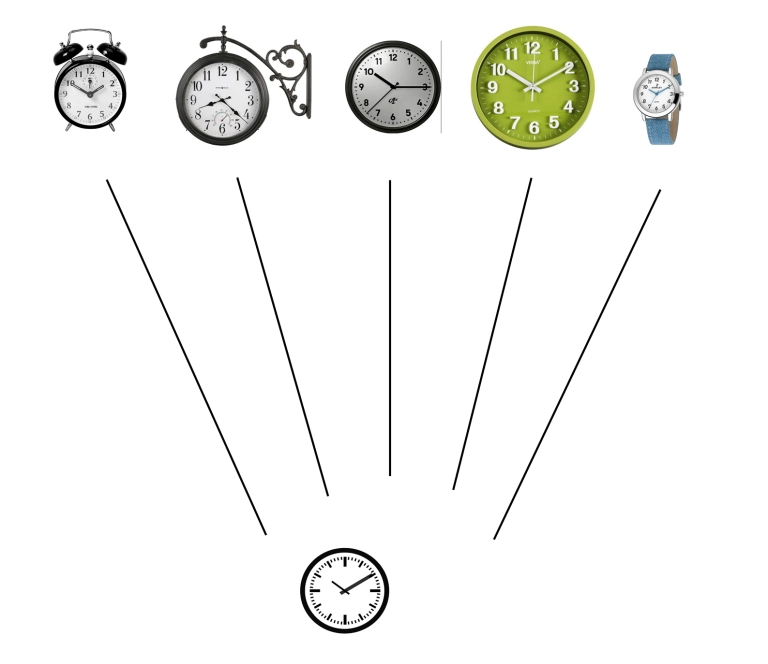

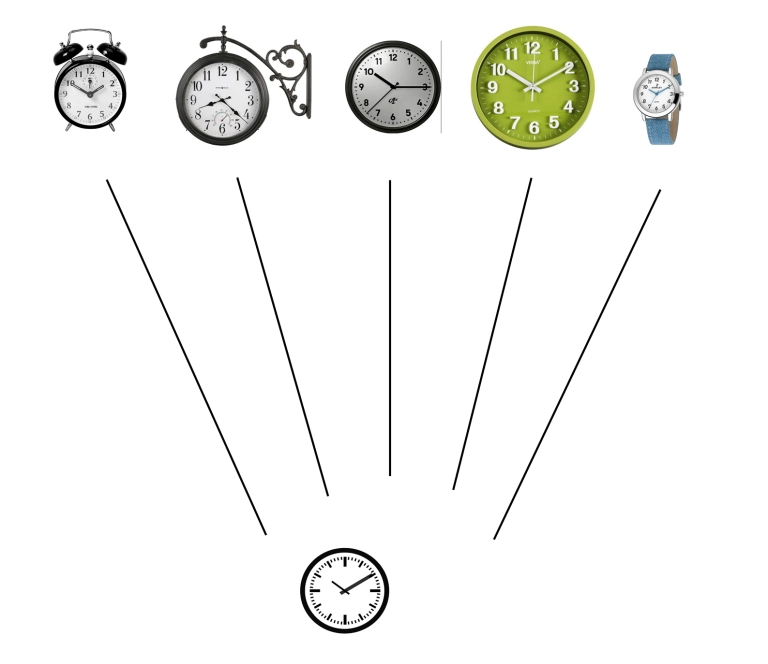

To achieve this, a good choice of a phenomenon, of a thing, is necessary in the first place, and for that I must be able to distinguish one thing from others with which it may be confused. I must see in my mind whether an apparent unit is actually composed of smaller ones and distinguish between similarities and differences that make subunits (such as the legs of a chair are subunits of the unit chair, or the fingers with respect to the hands) and supraunits (such as a chair is a supraunit with respect to its legs, seat and back, or the hands with respect to the fingers).

Thus, the concept of conceptualization:

[Joan Ferrer Gràcia (In: Heraclitus and Parmenides; full ref. in Spanish below)] Anyone associates thought with the elaboration and use of concepts. Therefore, in order to determine what thinking consists of, it will be necessary to reflect on what these concepts are: a representation that the human mind elaborates from the experience that the senses bring us to the world, and that contains the marks or characteristics that a whole series of things have in common. But, in the same way, thanks to their perceptive faculties, humans know concrete things and the characteristics that distinguish them from one another. Thanks to the mind, we compare these things with each other and elaborate concepts. Thanks to the senses, we know different apples. Thanks to the mind, we elaborate the concept <>, whose definition contains only those characteristics that all apples have in common and that distinguish them all from, for example, strawberries or peaches. Likewise, to elaborate the concept <> consists of comparing circles, triangles and squares, and then separating, from the series of characteristics that are proper to each of these figures, that other series of characteristics that all of them have in common. In this operation of abstraction - a word that means the act of separating some characteristics from others - consists the elaboration of a general concept. And in this elaboration of general concepts consists the task of thinking.

https://luisriesco.wordpress.com/2016/06/07/la-formacion-de-conceptos-2/

It is noteworthy that the conceptualization thus defined does not require words: by knowing objects never seen before, without knowing their names, a non-abstracted thought can conceptualize and distinguish between the general, the supra-unit, and the sub-units.

Imagine, reader, as a mental experiment, coming across a group of animals that you have never seen or heard of before: without naming them, you can see that they are a group of the same kind of animal, and even if you cannot notice differences in appearance among the animals, you can notice that there is more than one body: that is, even if those bodies were telepathically connected and constituted a single mind with multi-bodies, you would see units equal in everything, but a plurality, even before you had grasped the concept of that species or named the units that make it up.

(Another example of an unlearned concept: recognition of the impermanence of things in a melancholy way, as in contemplating the falling of flowers or thinking of the changing of the seasons; the reader has probably felt this feeling and never named it, or just named it melancholy, but this definition is even more specific; it has its term in Japanese).

Or, more simply, one may note the ability to understand similarities and differences between similar things in infants before they can speak.

Thus, although with limits to be discovered, there is in me a minimal ability to see the similar, see the differences, and see the union between the two in the same way that, as in the example of apples, I see the similarity between each one, see their differences in size, and their different places in space with no apparent connection, and see their union in the concept of units belonging to the same class of units (individual apples within the class apples, within the class fruits).

Translated with help from www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Hola a todos, este es mi primer post en esta comunidad. Es parte de una serie que estaba haciendo pero sus temas en esta parte encajan mejor aquí.

Tengo los siguientes principios: mi yo-mente existe, tengo un cuerpo, estoy rodeado de cosas –rodeado de Existencia, pues no soy lo único que existe–, decidir qué hacer con mi mente y mi cuerpo depende de mí, tengo las tres reglas morales provisionales de Descartes (ver aquí: https://peakd.com/hive-133872/@santiago-yocoy/una-moral-provisional-mientras-se-investiga-a-provisional-moral-while-investigating). Para saber qué es lo mejor que puedo hacer debo averiguar no por qué hay cosas, sino la naturaleza, la esencia, de qué son dos de ellas, mi mente y mi cuerpo. Pero, partiendo de la nada, no veo razón para creer que mi mente y mi cuerpo deban ser fundamentalmente distintos de cualesquiera otras cosas. Por lo tanto, me pregunto cuál es el mejor método o las mejores formas para conocer sobre las cosas en general.

Si fui más lejos que Descartes con una de las reglas de su método, veamos los méritos de las otras tres por si acaso puedo hacer lo mismo. La segunda puede ser llamada pensar analíticamente, la tercera sintéticamente, y la cuarta es registrar el mayor número de cosas posible.

Hay una interrelación entre estas y es que al analizar –al descomponer las cosas en tantas partes como sea posible– estoy descubriendo y registrando más cosas que las que se ofrecen a primera vista, estoy viendo el qué y el cuánto hay; y con la síntesis, descubro el cómo estaban unidas las cosas que analíticamente separé o cómo se relacionan con las demás aquellas que juzgue como inseparables en partes más pequeñas. De notar es que lo principal aquí para realizar las acciones es mi mente, con mi cuerpo siendo no más que un facilitador en ciertas tareas de exploración.

Ahora bien, estos principios no me dicen en sí mismos cómo llevarlos a cabo, ni a qué –dada la finitud del tiempo y de mi energía– dar prioridad. Pero yo ya tengo una prioridad, que es entender mi mente y mi cuerpo, y resulta que entre las cosas que existen están aquellas que claman que pueden ayudar para que lo logre. Ya he hablado de la religión (https://peakd.com/hive-133872/@santiago-yocoy/ensayo-pensamiento-cuerpo-y-dios-essay-thought-body-and-god), toca ahora hablar de la ciencia; supuestamente, según muchas personas, el mejor método para conocer.

En primera instancia, podría analizar definiciones más o menos formales de la ciencia. Una definición de libro de escuela primaria o secundaria diría algo por este estilo: ciencia es aquella actividad que utiliza un método específico, llamado consecuentemente científico, que consiste en observar un fenómeno, hacer una hipótesis (explicación provisional) sobre su naturaleza, llevar a cabo un experimento (hacer una cosa habiendo dicho antes que tendrá tal efecto sobre el fenómeno o por el fenómeno, por el lado predictivo; o para saber cómo se comporta ante ciertas cosas (una sustancia con otra), por el lado descriptivo) para comprobar la hipótesis, y si el experimento funciona tengo un hecho aislado o una teoría; una teoría es un conjunto de hechos sobre la realidad con relación lógica entre ellos que han sido comprobados experimentalmente; y si el experimento no cumple las expectativas, se descarta la hipótesis y se piensa en otra o se intenta pensar qué pudo haber salido mal en el experimento.

El método así descripto no contradiría las pocas asunciones que he adoptado hasta ahora; no obstante, veo que los problemas podrían estar en cómo elegir experimentos correctamente para saber si demuestran lo que quiero que demuestren, cómo saber que no hay interferencias de algún tipo sobre la porción de la Existencia que trato de apartar de las demás para su análisis.

Para lograrlo, una buena elección de fenómeno, de cosa, es necesaria en primer lugar, y para eso debo poder distinguir una cosa de otras con las que pueda confundirse. Debo ver en mi mente si una unidad aparente está compuesta en realidad por otras más pequeñas y distinguir entre similitudes y diferencias que hagan subunidades (como las patas de una silla son subunidades de la unidad silla, o los dedos respecto de las manos) y supraunidades (como una silla es una supraunidad respecto de sus patas, asiento y respaldo, o las manos respecto de los dedos).

Así, el concepto de conceptualización:

[Joan Ferrer Gràcia (En: Heráclito y Parménides)] Cualquier persona asocia el pensamiento con la elaboración y el uso de conceptos. Por lo tanto, para determinar en qué consiste pensar, habrá que reflexionar sobre qué son dichos conceptos: una representación que la mente humana elabora a partir de la experiencia que los sentidos nos aportan al mundo, y que contiene las marcas o características que toda una serie de cosas tienen en común. Pero, del mismo modo, gracias a sus facultades perceptivas, los humanos conocen las cosas concretas y las características que las distinguen entre sí. Gracias a la mente, comparamos estas cosas entre sí y elaboramos conceptos. Gracias a los sentidos, conocemos distintas manzanas. Gracias a la mente, elaboramos el concepto <>, cuya definición contiene solamente aquellas características que todas las manzanas tienen en común y que las distingue a todas ellas de, por ejemplo, las fresas o los melocotones. Asimismo, elaborar el concepto <> consiste en comparar círculos, triángulos y cuadrados, para después separar, de la serie de características que son propias de cada una de estas figuras, aquella otra serie de características que todas ellas tienen en común. En esta operación de abstracción –palabra que significa el acto de arrancar unas características de las otras– consiste la elaboración de un concepto general. Y en esta elaboración de conceptos generales consiste la tarea de pensar.

https://luisriesco.wordpress.com/2016/06/07/la-formacion-de-conceptos-2/

Es de notar que la conceptualización así definida no requiere de palabras: al conocer objetos nunca vistos antes, sin saber sus nombres puede conceptualizarse un pensamiento no apalabrado y distinguir entre lo general, la supraunidad, y las subunidades.

Imagine el lector, como experimento mental, que se cruza con un grupo de animales que jamás había visto ni oído hablar de ellos: sin ponerles nombre podrá ver que son un grupo de una misma clase de animal, y aun si no pudiera notar diferencias de aspecto entre los animales, sí podrá notar que hay más de un cuerpo: o sea, aun si esos cuerpos estuvieran conectados telepáticamente y constituyeran una sola mente con multicuerpos, vería unidades iguales en todo, pero una pluralidad, aun antes de apalabrar el concepto de esa especie o de nombrar las unidades que la conforman.

(Otro ejemplo de concepto no apalabrado: reconocimiento de la impermanencia de las cosas en una forma melancólica, como al contemplar la caída de flores o al pensar en el cambio de las estaciones; es probable que el lector haya sentido este sentimiento y nunca le haya puesto nombre, o apenas le haya puesto el de melancolía, pero esta definición es aun más específica; tiene su término en japonés).

O, más simplemente, puede notarse la capacidad de entender similitudes y diferencias entre cosas similares en los bebés antes de que puedan hablar.

Por lo tanto, aunque con alcances por descubrir, hay en mí una mínima capacidad de ver lo similar, ver las diferencias y ver la unión entre ambas del mismo modo que, como en el ejemplo de las manzanas, veo la similitud entre cada una, veo sus diferencias de tamaño, y sus distintos lugares en el espacio sin conexión aparente, y veo su unión en el concepto de unidades que pertenecen a una misma clase de unidades (manzanas individuales dentro de la clase manzanas, dentro de la clase frutas).

Referencias: Ferrer Gràcia, Joan. Heráclito y Parménides. Trad.: María Seguín. 2015, RBA

The rewards earned on this comment will go directly to the people( @santiago-yocoy ) sharing the post on Twitter as long as they are registered with @poshtoken. Sign up at https://hiveposh.com.

Thanks for posting in the community.

In your last paragraph you mention the similarity of apples and our inability to see the differences. THis is the way the brain works, we cannot actually comprehend the sheer scale of uniqueness, which is also why it is ridiculous to keep dividing ourselves socially among differences, rather than using larger buckets of traits to understand imperfectly, but with more practical application.

"which is also why it is ridiculous to keep dividing ourselves socially among differences, rather than using larger buckets of traits to understand imperfectly, but with more practical application."

I shall arrive to that 👍; I'm displaying epistemological foundations for peace and cooperation

Of course, as a Reality Master I totally agree with the need to recognise the tools we have at our disposal and to learn how to use them effectively. I know Jiddu Krishnamurti would certainly encourage your explorations into self-knowledge.

This is admirable work, but we must also consider whether it is worth re-creating the wheel so to speak in this way, or whether we could instead short-cut the process and intuit the truth from the works of previous explorers of these topics. May our time and efforts then be better served in exploring the deeper aspects of these topics?

(I should also recognise that some inventors are indeed recreating the wheel in attempts to improve on the age-old design.)

Every generation must relearn the truths the old ones have found, or find their mistakes.

I certainly do not ignore old wisdom, though I've yet to learn, but I have studied some of the oldest recorded philosophy: Parmenides, Heraclitus, Lao Tsé, as well as several not so old

Congratulations @santiago-yocoy! You have completed the following achievement on the Hive blockchain And have been rewarded with New badge(s)

Your next target is to reach 200 replies.

You can view your badges on your board and compare yourself to others in the Ranking

If you no longer want to receive notifications, reply to this comment with the word

STOPCheck out our last posts:

Support the HiveBuzz project. Vote for our proposal!