Unas de las historias más interesantes del siglo XX

No matter how much we know or think we know about things, all our knowledge, all our information, is nothing more than a drop in the middle of the ocean. There's so much to know, there are so many stories that exist that one can always be surprised to discover something new (for one) and that it is actually an old and widely known story (for others). Until yesterday afternoon I had no idea who Leni Riefenstahl was and after watching this documentary I asked myself, "How come I didn't know?"

No importa cuánto sepamos o creamos saber de las cosas, todo nuestro conocimiento, toda nuestra información, no es más que una gota en medio del océano. Es tanto lo que hay por saber, son tantas las historias que existen que siempre puede uno sorprenderse de descubrir algo nuevo (para uno) y que en realidad es una historia vieja y ampliamente conocida (para otros). Hasta ayer por la tarde no tenía la menor idea de quién había sido Leni Riefenstahl y después de haber visto este documental me pregunté, "¿Cómo es que no lo sabía?"

Today we have great female directors: Sofia Coppola, Carla Simón, Greta Gerwig, Jane Campion, Chloé Zhao, Kathryn Bigelow, Maite Alberdi and many more. A few decades ago there were few women who stood out in a world almost monopolized by the male presence, hence the work of Agnés Varda is doubly important, not only for her extraordinary talent but also for the space she carved for future generations of female directors. But before Varda, back in 1934, there was a woman who, in the best style of the great directors of the past, wrote, directed and starred in Das blaue Licht (The Blue Light), a film adaptation of a novel by Gustav Renker that won her the Silver Medal at the Venice Film Festival. This woman was Leni Riefenstahl. Previously known for starring in a series of mountaineering films directed by Arnold Fanck, Leni's debut feature behind the lens astonished not only audiences but also genre connoisseurs - where had she learned to direct like this, how did she achieve such sequences as the protagonist's mountain climb? If you watch The Blue Light it's impossible not to recognize the director's talent and it's hard to understand that it was the first film directed by a woman who was barely over thirty years old. The filming techniques used are innovative, Leni's talent has been there for all to see since that first film, so what happened? Why is there a shadow that covers not only the work of this woman but also her personal life? Hitler. That's what happened: Nazism came to power.

Hoy día tenemos grandes directoras de cine: Sofia Coppola, Carla Simón, Greta Gerwig, Jane Campion, Chloé Zhao, Kathryn Bigelow, Maite Alberdi y muchas más. Hace algunas décadas eran pocas las mujeres que destacaban en un mundo casi monopolizado por la presencia masculina, de allí que la obra de Agnés Varda sea doblemente importante, no sólo por su extraordinario talento sino además por el espacio que labró para las futuras generaciones de directoras. Pero antes de Varda, por allá en el lejano año de 1934 hubo una mujer que al mejor estilo de los grandes directores de antes escribió, dirigió y protagonizó Das blaue Licht (The Blue Light), adaptación cinematográfica de una novela de Gustav Renker que le valió la medalla de Plata en el Festival de Venecia. Esta mujer fue Leni Riefenstahl. Previamente conocida por protagonizar una serie de películas de alpinismo dirigidas por Arnold Fanck, la ópera prima de Leni detrás del lente maravilló no sólo al público sino también a los entendidos del género, ¿dónde había aprendido a dirigir así? ¿cómo logró esas secuencias como la de la escalada de la protagonista en la montaña? Si se ve The Blue Light resulta imposible no reconocer el talento de la directora y cuesta entender que se tratara de la primera película dirigida por una mujer que apenas pasaba los treinta años. Las técnicas de filmación utilizadas son innovadoras, el talento de Leni está a la vista de todos desde esa primera película, entonces ¿qué pasó? ¿por qué hay una sombra que cubre no sólo la obra de esta mujer sino también su vida personal? Hitler. Eso fue lo que pasó: el nazismo llegó al poder.

And it's not that Leni was Jewish - she was a pure German, blonde, with blue eyes and a very German last name - and the Third Reich condemned her work, but quite the opposite. After being delighted with her first film, the Nazi party authorities contacted her to film the famous patriotic congress of 1934 in which the Nazis, led by Adolf Hitler who was already in power, exalted the values of the German people. And the Aryan race, could she reject the offer? Could one then know what would happen next? Was there anyone in Germany at that time who had refused to collaborate with the party that had restored hope and breathed a nationalist spirit into the people?

Y no es que Leni fuera judía - era una alemana de pura cepa, rubia, de ojos azules y un apellido muy alemán - y el Tercer Reich condenara su obra sino todo lo contrario. Después de haber quedado encantados con su primera película, las autoridades del partido Nazi la contactaron para que filmara el famoso congreso patriótico de 1934 en el que los nazis, encabezados por un Adolf Hitler que ya estaba en el poder, exaltan los valores del pueblo alemán y la raza aria, ¿podía ella rechazar la oferta? ¿podía saber entonces lo que ocurriría después? ¿había en ese momento en Alemania alguien que se hubiera negado a colaborar con el partido que había devuelto la esperanza e insuflado un espíritu nacionalista en el pueblo?

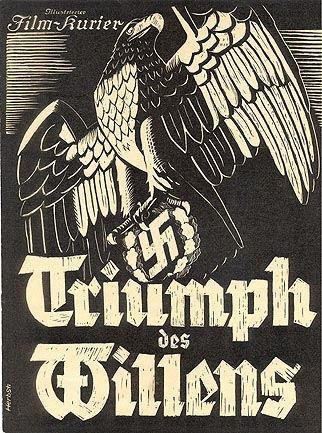

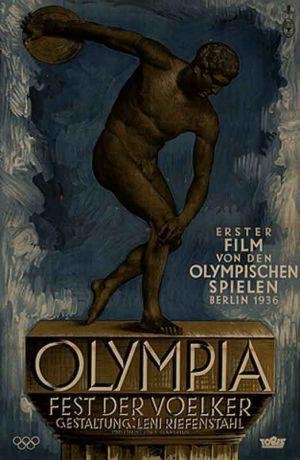

The result of that work was the documentary Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will) that earned her a Gold medal at the Venice Festival, but his filmic and aesthetic consecration came with the documentary she made about the Olympic Games held in the city of Berlin in 1936 and which has an extension of almost 230 minutes, divided into two parts. The work was celebrated for its way of honoring the beauty of the human body and for once again challenging the conventional nature of documentary film at the time. As a historical document and as film study material it's worthy of review, but is it possible to praise that film today? This is where Riefenstahl's story gets a little rocky, murky, controversial and contradictory. Leni filmed four documentaries for the Nazis, she also filmed Hitler's military advance on Poland at the beginning of the war, she dealt directly and recurrently with Adolf Hitler, Josef Goebbels, Hermann Göring, Albert Speer, she declared herself a supporter of national socialism and However, whenever she was interrogated and questioned about the atrocities of the Nazi concentration camps, the German director swore she knew nothing about it. Its not credible because it seems implausible, but is it possible? Is it possible that, concentrated on her work and in the bubble of what was her media life, she had not known anything about what was happening beyond the borders of Germany? Did no one say anything to her at that time? Didn't her have any suspicions?

El resultado de ese trabajo fue el documental Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will) que le valió una medalla de Oro en el Festival de Venecia, pero su consagración fílmica y estética llegó con el documental que hizo sobre los Juegos Olímpicos celebrados en la ciudad de Berlín en 1936 y que tiene una extensión de casi 230 minutos, divididos en dos partes. La obra fue celebrada por su manera de honrar la belleza del cuerpo humano y por desafiar nuevamente lo convencional que era el cine documental en la época. Como documento histórico y como material de estudio cinematográfico es digno de revisión, pero ¿es posible alabar esa película hoy día? Es aquí donde la historia de Riefenstahl se pone algo escabrosa, turbia, controversial y contradictoria. Leni filmó cuatro documentales para los nazis, filmó también el avance militar de Hitler sobre Polonia al inicio de la guerra, trató directa y recurrentemente con Adolf Hitler, Josef Goebbels, Hermann Göring, Albert Speer, se declaró a sí misma partidaria del nacional socialismo y sin embargo siempre que fue interrogada y cuestionada por las atrocidades de los campos de concentración nazis, la directora alemana juró no saber nada al respecto. No es creíble porque parece inverosímil, pero ¿es posible? ¿es posible que concentrada en su trabajo y en la burbuja de lo que era su vida mediática no hubiera sabido nada de lo que sucedía más allá de las fronteras de Alemania? ¿nadie le dijo nada en ese momento? ¿no tuvo ninguna sospecha?

And that leads us to a central dilemma in the work of any artist. Leni was hired by the Nazi party to film the documentaries because she was talented and because that was her job: making films. You can argue that it was just one assignment (or well, several) and that she limited herself to doing her job and getting paid, but is it possible to do that in a context like that? Should the artist consider the political and social impact of his/her work? Or should one limit oneself to the expression of art? Whenever she was interviewed throughout her life, Leni would get very upset when people tried to ask her political questions. She even canceled interviews because she felt they were going to make her look like a neo-Nazi, but wasn't she? Can the analysis of her talent as a filmmaker be dissociated from her affinity with National Socialism? Can we separate the work of the artist, admire the art and condemn the person?

Y eso nos conduce a un dilema central en la obra de cualquier artista. Leni fue contratada por el partido Nazi para filmar los documentales porque tenía talento y porque ese era su trabajo: hacer cine. Puede argumentar que era sólo un encargo (o bueno, varios) y que ella se limitó a cumplir su trabajo y cobrar, pero ¿es posible hacer eso en un contexto como aquel? ¿debe el artista considerar el impacto político y social de su labor? ¿o debe limitarse a la expresión de su arte y de cumplir su trabajo? Siempre que fue entrevistada a lo largo de su vida, Leni se molestaba mucho cuando intentaban hacerle preguntas de política. Incluso llegó a cancelar entrevistas por sentir que la iban a hacer ver como una neonazi, pero ¿acaso no lo era? ¿puede disociarse el análisis de su talento como cineasta de su afinidad con el nacionalsocialismo? ¿podemos separar la obra del artista, admirar su arte y condenar su persona?

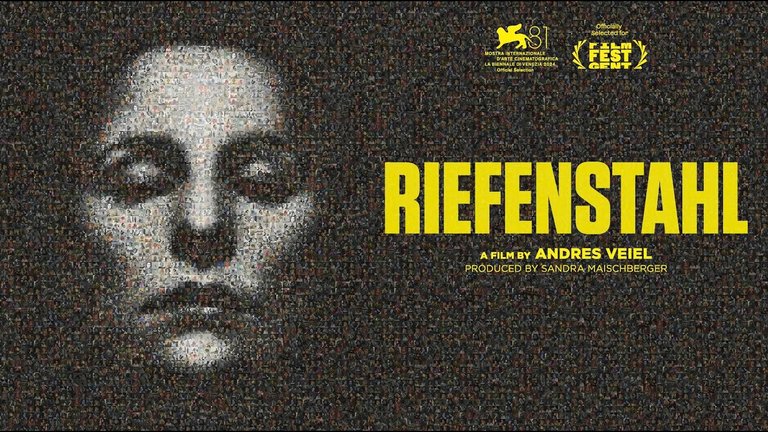

Years after Leni Riefenstahl's death in 2003 (at the age of 101!) journalist Sandra Maischberger (who had interviewed her on the occasion of her 100th birthday) had access to review more than 7,000 boxes containing Leni's legacy in order to inventory it and make a documentary. Andres Veiel joined the project as director and the challenge was to tell the story of this controversial woman being objective and impartial, but without being untruthful. Using archival footage, unpublished Super 8 recordings, audio, personal photographs and several interviews, Veiel shows us the life and work of a Leni Riefenstahl, sometimes fragile, sometimes violent, but always enigmatic. Perhaps the most direct reaction is to condemn her as a pariah for having been associated with Hitler and his officers and for having helped to brainwash and clean up the image of a regime that did so much damage, but on the other hand, what must it be like to live in the utter contempt of the entire world for almost sixty years? It's not just that they asked her if she knew about the concentration camps in an interview, they did it over and over again throughout her life, how could that not affect her, how could it not be taken into account that all her talent was overshadowed by the context? Yes, she filmed for the Nazis, but she was also a woman who, at a time and in a man's world, revolutionized documentary filmmaking. In addition, Leni Riefenstahl was tried at Nuremberg and was not convicted, she was never affiliated with the Nazi party, is it possible that she really did not know anything? And more importantly, are you innocent when you don't know? I read you in the comments.

Años después de la muerte de Leni Riefenstahl en 2003 (¡a los 101 años de edad!) la periodista Sandra Maischberger (quien le había hecho una entrevista con el motivo de su centenario) tuvo acceso a la revisión de más de 7.000 cajas que contenían el legado de Leni para inventariarlo y hacer un documental. Al proyecto se unió Andres Veiel en calidad de director y el desafío era lograr contar la historia de esta controversial mujer siendo objetivo e imparcial, pero sin faltar a la verdad. Utilizando imágenes de archivo, grabaciones inéditas en Super 8, audios, fotografías personales y varias entrevistas, Veiel nos muestra la vida y obra de una Leni Riefenstahl a veces frágil, a veces violenta, pero siempre enigmática. Quizás la reacción más directa sea condenarla como un paria por haberse relacionado con Hitler y sus oficiales y por haber ayudado a lavar cerebros y a limpiar la imagen de un régimen que hizo tanto daño, pero por otro lado, ¿cómo debe ser vivir en el total desprecio del mundo entero durante casi sesenta años? No es sólo que le hayan preguntado si sabía sobre los campos de concentración en una entrevista, sino que lo hicieron una y otra vez durante toda su vida, ¿cómo podría no afectarla eso? ¿cómo no tener en cuenta que todo su talento quedó eclipsado por el contexto? Sí, filmó para los nazis, pero también fue una mujer que en una época y en un mundo de hombres, revolucionó el cine documental. Sumado a ello, Leni Riefenstahl fue juzgada en Nuremberg y no fue condenada, nunca estuvo afiliada al partido nazi, ¿es posible que en verdad no hubiera sabido nada? Y lo que es más importante: ¿se es inocente cuando no se sabe? Los leo en los comentarios.