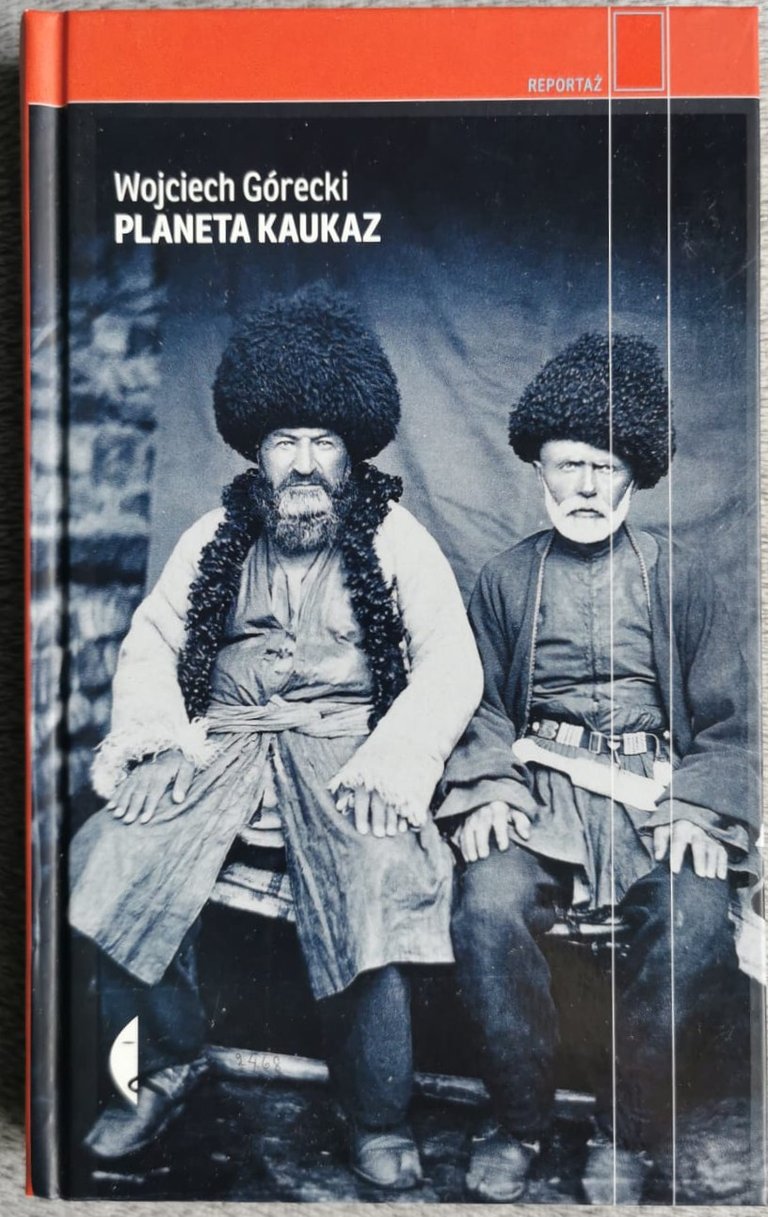

| Powróciłem na Kaukaz, a to znaczy, że i w serii czytelniczej pora na powrót do tego regionu – bo takie właśnie książki sobie w podróż zabrałem. Konkretnie to zestaw wschodni Wojciecha Góreckiego – trylogię kaukaską uzupełnioną jeszcze jedną, bardziej wschodnią pozycją tego autora. Ale na początek będzie pierwsza część trylogii, czyli – „Planeta Kaukaz”. Reportaże w niej zawarte opisują niezwykłą różnorodność Kaukazu Północnego – miejsca, w którym jeszcze nie byłem i do którego, prawdopodobnie, nieprędko dotrę, biorąc pod uwagę sytuację geopolityczną. Z tym większym więc zaciekawieniem zabrałem się za lekturę. | I've returned to the Caucasus, which means it's time for me to return to the region in my reading series, too - because I have picked up just such books for the journey. Specifically, it's Wojciech Górecki's Oriental Set - the Caucasus trilogy followed by another, even more eastern item by this author. But I will begin with the first part of the trilogy, namely - ‘The Planet Caucasus’. The reportages it contains describe the extraordinary diversity of the North Caucasus - a place I have not yet been to and which, given the current geopolitical situation, I am unlikely to get to any time soon. So it was with all the more curiosity that I started reading. |

| Powiedzmy to jasno od samego początku – książka nie należy do najgrubszych (niespełna 240 stron) i praktycznie o każdym z opisanych w niej regionów Kaukazu dałoby się spokojnie napisać nawet i dwa razy tyle, nie wyczerpując przy tym tematu. Siłą rzeczy dostajemy więc jedynie wycinek obrazu całości, wycinek widziany oczami Góreckiego i jego rozmówców – przyjaciół, znajomych, czasem po prostu obcych spotykanych przelotnie podczas podróży. | Let us make it clear from the very beginning - the book is not the thickest (less than 240 pages) and one could easily write twice as much about each of the Caucasus regions described in it, without exhausting the subject. Naturally, we only get a fragment of the whole picture, a fragment seen through the eyes of Górecki and his interlocutors - friends, acquaintances and sometimes just strangers met in passing during the journey. |

| Przy czym, jak to u dobrych reporterów bywa – ten wycinek okazuje się wystarczająco szeroki, by dać nam, czytelnikom, poczucie, że i my tam byliśmy, że i my doświadczyliśmy, przynajmniej w jakimś stopniu, tego, co się tam działo. Górecki prowadzi nas krok po kroku, region po regionie, przez cały Kaukaz Północny (a nawet odrobinę dalej) i przybliża nam to niezwykłe miejsce. | However, as is often the case with good reporters, this fragment turns out to be broad enough to give us, the readers, the feeling that we were there too, that we experienced, at least to some extent, what happened there. Górecki takes us step by step, region by region, through the entire North Caucasus (and even a little further) and brings us closer to this extraordinary place. |

| Jego opowieść jest podzielona na 14 części głównych – rozdziałów uzupełnionych o późniejsze notatki, plus wstęp i zakończenie. Poszczególne tytuły brzmią dla polskiego czytelnika egzotycznie, niejako zachęcając w ten sposób dodatkowo do lektury. A będą to, po kolei: | His story is divided into 14 main parts - chapters supplemented by later notes, plus an introduction and conclusion. The individual titles sound exotic to the foreign reader, in a way further encouraging reading. And they will be, one by one: |

| - „Elbrus” – trudno pisać o Kaukazie nie wspominając o jego najwyższym szczycie. O tym, jak ludzie próbowali go zdobywać, z jakimi – czasami – tragediami się to wiązało, i o tym, jak postępują obserwacje wulkanu, uważanego za wygasły. | - ‘Elbrus’ - it is difficult to write about the Caucasus without mentioning its highest peak. And how people tried to conquer it, what - sometimes - tragedies this involved, and how the observations of the volcano, thought to be extinct, are progressing. |

| - „Miraż” – Kałmucja i jej specyfika. Miejsce, w którym - czasami - łatwiej o czarny kawior, niż o chleb. W którym wciąż jeszcze można usłyszeć „Dżangar” śpiewany przy dźwiękach dombry. I w którym łaskawie panujący przywódca, przedstawiany jako wcielenie Wisznu, oficjalnie ustanawia Koncepcję Myślenia Etnoplanetarnego, przekonany, że spotkał kosmitów i zwiedzał latający talerz. | - ‘Mirage’ - Kalmykia and its peculiarities. A place where, sometimes, it is easier to get black caviar than bread. Where it is still possible to hear ‘Jangar’ sung to the sound of dombra. And where the graciously reigning leader, heralded as an incarnation of Vishnu, officially establishes the Concept of Ethnoplanetary Thinking, convinced that he has met aliens and visited a flying saucer. |

| - „Lezginka” – czyli Dagestan. Skrajny tygiel narodowości, które lepiej lub gorzej muszą funkcjonować w ramach jednego państwa. Autobus zatrzymany serią z automatu gdzieś pod Chasawjurtem. Kaukaska gościnność i machyzm dżygitów – czasami tylko pozorny. Resztki tradycyjnych obyczajów, pozwalające wciąż jeszcze zachowywać odrębność poszczególnych narodów. | - ‘Lezginka’ - in other words, Dagestan. An extreme melting pot of nationalities that, for better or worse, have to function within a single state. A bus stopped by a series from a machine gun somewhere near Khasavyurt. The Caucasian hospitality and machismo of the dzhigits - sometimes only illusory. The remnants of traditional customs, allowing the distinctiveness of individual nations to still be preserved. |

| - „Hinalug” – wieś Xınalıq położona wysoko wśród gór Azerbejdżanu, jedna z najwyżej położonych w Europie. Około 2000 mieszkańców, mających swój własny, mocno odrębny od sąsiednich, język i równie odrębne obyczaje. Skazanych na nieuniknioną utratę tożsamości, powolną wraz z doprowadzeniem do wsi pierwszej drogi w latach 70 XX wieku, obecnie przyspieszającą po jej wyasfaltowaniu i ułatwieniu dostępu turystom. | - ‘Xınalıq’ - Xınalıq village located high among the mountains of Azerbaijan, one of the highest located in Europe. Some 2,000 inhabitants, with their own language and customs, strongly distinct from those of their neighbours. Doomed to an inevitable loss of identity, firstly slow with the bringing of the first road to the village in the 1970s, now accelerating after it was asphalted and made more easily accessible to tourists. |

| - „Zikr” – o trudnej i skomplikowanej historii Czeczenów, ich wiekowej historii oporu przeciwko rosyjskim najeźdźcom i o tym, jak wielką rolę w ich życiach odgrywa struktura klanowo-plemienna, odwieczne Prawo i umiłowanie wolności graniczące z anarchią. I o tym, jak władzę w tym kraju przejął ród Kadyrowów. | - ‘Dhikr’ - about the difficult and complicated history of the Chechens, their centuries-long history of resistance against Russian invaders and how the clan-tribal structure, the age-old Law and a love of freedom reaching almost anarchy level play a crucial role in their lives. And about how the Kadyrov family seized power in the country. |

| - „Magas” – o bliskich krewnych Czeczenów – Inguszach. O tym, jak Rosja umiejętnie wykorzystywała napięcia między nimi, a Osetyjczykami, by móc trzymać w szachu obie republiki. O tym, jak budowali tytułowy Magas – własną stolicę, w końcu własnej republiki. I jaką rolę w tym wszystkim odegrał teatr. | - ‘Magas’ - about the close relatives of the Chechens - the Ingush. About how Russia skilfully exploited tensions between them and the Ossetians to be able to hold both republics in check. About how the Ingush built Magas - their own capital, eventually of their own republic. And what role theatre played in all this. |

| - „Darial” – tym razem Osetia Północna. O tym, jak Osetyńczycy próbowali budować własną tożsamość historyczną, sięgając nieraz do skrajnych absurdów, takich jak przypisywanie swojemu narodowi postać niejakiego Joszo Czyryszti, czyli Jezusa. Jak w ich narodzie odbijają się kaukaskie „najnaizm” i „samość” – czyli przekonanie, że to właśnie konkretny naród jest najstarszy, najlepszy, najbardziej pokrzywdzony, a by mógł się rozwinąć, musi się rządzić sam i sam napisać własną historię. Jest też próba wyjaśnienia, czemu Osetyjczycy, w przeciwieństwie do innych kaukaskich narodów, nie buntowali się, lecz współpracowali z Rosjanami. | - ‘Darial’ - this time North Ossetia. About how the Ossetians tried to build their own historical identity, sometimes reaching for extreme absurdities, such as attributing to their nation the figure of a certain Yosho Chirishti, in other words Jesus. How Caucasian ‘themostism’ and ‘ourselfness’ - that is, the belief that a particular nation is the oldest, the best, the most disadvantaged, and that in order to develop, it must govern itself and write its own history - is reflected in their nation. There is also an attempt to explain why the Ossetians, unlike other Caucasian peoples, did not rebel but cooperated with the Russians. |

| - „Uastyrdży” – też Osetia, tylko Południowa. O ponurej rzeczywistości Cchinwali lat 90, gdzie na każdym kroku czaiło się nieznane, i nigdy nie można było być pewnym, czy trafi się na tradycyjną kaukaską gościnność, czy może niemal równie tradycyjny kaukaski rabunek. O Uastyrdżim – pogańskim bóstwie do dziś czczonym i szanowanym przez naród… i o tym, jak niewiele – oprócz Rosji – potrzeba, by przyjaźń między narodami zmieniła się w nienawiść. | - ‘Uastyrdzhi’ - also Ossetia, but the South one. About the grim reality of 1990s Tskhinvali, where the unknown lurked at every turn, and you could never be sure whether you would encounter traditional Caucasian hospitality or almost equally traditional Caucasian robbery. About Uastyrdzhi - a pagan deity still worshipped and revered by the people today... and about how little - apart from Russia - it takes for friendship between nations to turn into hatred. |

| - „Czerkieska” – opowiada o Kabardo-Bałkarii i Karaczajo-Czerkiesji, tworach szatańskich knowań radzieckich polityków. Mieli oni cztery narody, spokrewnione w parach. Z jednej strony kaukaskich Kabardyjczyków i Czerkiesów, z drugiej – turkijskich Karaczajów i Bałkarów. W idealnym świecie powstałyby Kabardyno-Czerkiesja i Karaczajo-Bałkaria. A w naszym – połączono te narody na krzyż, jeszcze bardziej nasilając historyczną niechęć między nimi, by skuteczniej nimi rządzić. Całość ukazana przez pryzmat wyborów prezydenta Karaczajo-Czerkiesji. | - ‘Chokha’ - tells the story of Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay-Cherkessia, the creations of the fiendish intrigues of Soviet politicians. They had four nations, related in pairs. On one side, the Caucasian Kabardins and Cherkess, on the other, the Turkic Karachays and Balkars. In an ideal world, Kabardino-Cherkessia and Karachay-Balkaria would have been formed. But in ours, these nations were joined crosswise, further intensifying the historical resentment between them in order to govern them more effectively. All shown through the lens of the Karachay-Cherkessia presidential election. |

| - „Szoana” – też Karaczajo-Czerkiesja, obchody uroczystości Świętego Jerzego w Chumarze, w cerkwi na górze Szoana. Ich historia, prześladowania za czasów radzieckich, trzeba przyznać – niezwykle kreatywne (na przykład konfiskowanie butów pielgrzymom) – i czasy współczesne, gdy do cerkwi przybywają tysiące ludzi, z różnych kaukaskich narodów, by zgodnie oddać cześć świętemu smokobójcy. | - ‘Shoana’ - also Karachay-Cherkessia, the celebration of the feast of Saint George in Khumara, in the Orthodox church on Mount Shoana. Their history, the persecutions during the Soviet era, it must be said - extremely creative (confiscating pilgrims' shoes, for example) - and the modern times, when thousands of people, from various Caucasian nations, come to the Orthodox church to worship the holy dragonslayer in unison. |

| - „Machadżyrowie” – o smutnym losie Adygów, Czerkiesów, Szapsugów przegnanych w XIX wieku z ich odwiecznych ziem i zmuszonych do emigracji – głównie do Imperium Osmańskiego, ale też w dalsze części Europy, czy nawet do Ameryk. Jak smutny był to los, mówi fakt, że w ciągu stu lat liczba Adygów na Kaukazie zmniejszyła się dwudziestokrotnie… A ci, którzy przetrwali, doświadczali i do dziś doświadczają rusyfikacji. Plus legenda o bogu Telepinie. | - ‘The Makhajirs’ - about the sad fate of the Adyghe, Cherkes, Shapsug people chased away from their ancestral lands in the 19th century and forced to emigrate - mainly to the Ottoman Empire, but also to further parts of Europe or even to the Americas. What a sad fate this was, is illustrated by the fact that within a century the number of Adyghe in the Caucasus decreased twentyfold... And those who survived, experienced and still experience Russification. Plus the legend of the god Telepin. |

| - „Raskolnicy” – o rosyjskich starowiercach, którzy przetrwali jeszcze w niektórych kaukaskich osadach. Niekrasowcy, przegnani z Rosji przez carat, wrócili po rewolucji, by ratować się przed asymilacją w tureckiej Anatolii. Być może z deszczu pod rynnę – łatwiej było zachować tożsamość wśród obcych, Turków – niż wśród swoich – Rosjan. Oprócz nich żyją na Kaukazie jeszcze mołokanie, pryguni, maksymiści… lecz nawet o muzeum, chroniące pamiątki przeszłości i świadectwa dawnej tożsamości, nie jest łatwo. | - ‘The Raskolniks - about Russian Old Believers who have survived still in some Caucasian settlements. The Nekrasov Cossacks, chased out of Russia by the tsarism, returned after the revolution to save themselves from assimilation in Turkish Anatolia. Perhaps from the rain to the gutter - it seems that it was easier to maintain an identity among strangers, the Turks - than among their own, the Russians. Apart from them, there are still Molokans, Pryguns and Maximists living in the Caucasus... but it is not easy even to establish a museum protecting the mementos of the past and the testimonies of the old identity. |

| - „Atamani” – o Kozakach, ale nie tych z ukraińskiego Zaporoża, lecz o rosyjskich kozakach dońskich, kubańskich, tereckich… O tym, jak ruch kozacki odrodził się po latach przytajenia w czasach radzieckich, przysparzając nie takich znowu małych problemów nowopowstałemu państwu rosyjskiemu – i jak ponownie przygasł, rozpraszając się na armię, firmy ochroniarskie, mafię… I o tak zwanych tradycyjnych rosyjskich wartościach, w oczywisty sposób uważanych za znacznie lepsze od zgniłych zachodnich, pełnych makdonaldów i pornografii. | - ‘The Atamans’ - about Cossacks, but not the ones from Ukrainian Zaporizhzhia, but the Russian Cossacks of the Don, Kuban and Terek regions... About how the Cossack movement was revived after years of obscurity in Soviet times, causing not so small problems for the newly formed Russian state - and how it dimmed again, dispersing into the army, security companies, the mafia... And about so-called traditional Russian values, obviously considered much better than the rotten Western ones, full of macdonalds and pornography. |

| - „Apsuara” – o Abchazach i o tym, jak w ich życiach przeplata się współczesność z tradycją. Ilustrowane sceną spotkania Ławrika z rodu Achbów z Astamurem z rodu Łakerbajów, którzy na świętym uroczysku, w obecności kapłana mieli rozwiązać sprawę klątwy za przewinę sprzed sześćdziesięciu lat… | - ‘The Apsuara - about the Abkhazians and how modernity and tradition are intertwined in their lives. Illustrated by a scene of a meeting between Lavrik of the Akhba clan and Astamur of the Lakerbaia clan, who, in a sacred site in the wilderness, in the presence of a old beliefs priest, were to settle the case of a curse for an offence from sixty years ago... |

| Trudno jest pozostać obojętnym na tę lekturę. Pozwala ona zrozumieć wiele rzeczy i spraw, które dla nas, w Europie, mogą nie być oczywiste. Przede wszystkim to, jak bardzo skomplikowanym światem jest Kaukaz i dlaczego tak trudno jest, by zapanował na nim pokój. Ale także też to, że dla wielu mniejszych narodów i społeczności poważniejszym zagrożeniem, niż atakujący z północy rosyjski niedźwiedź – przed którym można próbować znaleźć schronienie w górskich dolinach – stają się telewizja, internet, asfalt i nadchodzące razem z nimi – globalizacja i moda, sprzyjające i ułatwiające zanik lokalnego języka, tradycji, zwyczajów (dla sprawiedliwości – czasem, ale niestety znacznie rzadziej, również ratowanie ich). Czy potomkom dzielnych i dumnych kaukaskich górali uda się przetrwać, zachować własną tożsamość i, być może, kiedyś znowu panować we własnym domu? Największe narody – taką szansę mają. Mniejszym, liczącym po kilkaset osób, będzie bardzo trudno, choć oczywiście mam nadzieję, że również i one przetrwają. Ale po lekturze trudno o szczególnie optymistyczne nastawienie… | It is difficult to remain indifferent to this reading. It allows one to understand many things and issues that may not be obvious to us outside Caucasus. First of all, how complicated the Caucasus is and why it is so difficult to bring peace and friendship to it. But also the fact that, for many smaller nations and communities, a more serious threat than the Russian bear attacking from the north - from which one can try to find refuge in the mountain valleys - are becoming television, the internet, asphalt and coming with them - globalisation and modern trends, fuelling and facilitating the disappearance of local languages, traditions and customs (and, to be fair, sometimes, but unfortunately much less frequently, also their salvation). Will the descendants of the brave and proud Caucasian highlanders manage to survive, preserve their own identity and, perhaps, one day reign again in their own home? The largest nations - they have that chance. For the smaller ones, consisting of a few hundred people each, it will be very difficult, although of course I hope they will also survive. But it is difficult to be particularly optimistic after reading.... |

| Co się tyczy samej książki, mogę o niej pisać wyłącznie w samych superlatywach. Autor ma wszelkie cechy dobrego reportera – nie boi się pozyskiwać wiedzy u samych źródeł, w terenie, potrafi docierać do interesujących rozmówców, którzy są w stanie pokazać mu lokalną perspektywę i punkt widzenia, a następnie opisać to wszystko w sposób barwny i żywy, przyciągający uwagę czytelnika od początku do końca. Końca wyrażonego często jednym, dwoma zdaniami, zmuszającymi do zastanowienia, zamyślenia, zadumy. Taki reporter nawet w pozornie nudnym, nieciekawym miejscu jest w stanie znaleźć chwytliwy temat i zrobić z niego świetny materiał. A przecież ostatnie, co można powiedzieć o Kaukazie to to, że jest nudny… Krótko mówiąc, „Planeta Kaukaz” to książka, którą mogę z czystym sumieniem polecić każdemu, kto chce ten kawałek świata poznać lepiej, a może nawet i trochę zrozumieć. Ode mnie – chorego na Kaukaz chyba nieuleczalnie – ocena maksymalna. | As for the book itself, I can only write about it in superlatives. The author has all the qualities of a good reporter - he is not afraid to obtain knowledge from the very sources, in the field, he is able to reach interesting interlocutors who are capable of showing him the local perspective and point of view, and then to describe it all in a colourful and vivid way that holds the reader's attention from beginning to end. An end often expressed in one or two sentences, forcing the reader to think, to ponder, to reflect. Such a reporter is able, even in a seemingly dull, uninteresting place, to find a catchy subject and make great material out of it. And after all, the last thing you can say about the Caucasus is that it is boring... In short, ‘Planet Caucasus’ is a book I can in good conscience recommend to anyone who wants to get to know this part of the world better, and maybe even understand it a little. From me - probably incurably ill with the Caucasus - a maximum rating. |

That sounds very interesting

Thank you! Unfortunately I'm not sure, if it has been translated to English already :( But the book itself is definitely worth reading, and I hope I'll be able to prepare reviews for the next parts of the trilogy soon.