Tl;dr: Skip to bottom and have a listen to end results

Here's a post literally nobody asked for! I have an evening to myself so what better way to parrrrtayyy on downnnnnn by... writing some 18th century four-part chorale harmony and writing a blog about how I did it?

This is actually something I do for my job as a music teacher, and although it's part of the curriculum of AP Music Theory in the USA, it's kind of an obsolete method for these days.

Figured Bass

Historically, Figured bass is essentially a way of composition. You provide the bassline of music alone, with a few numbers underneath which represent some instructions. It would then be the job of the musician to 'realise' the other 3 musical lines that are implied based on only this information - often improvised on the spot!

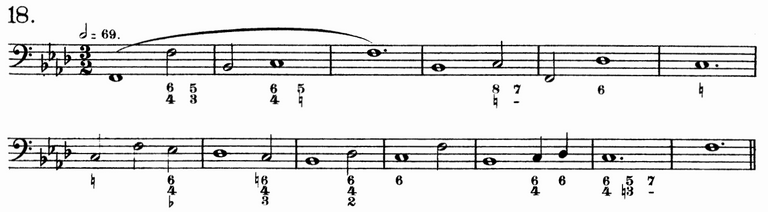

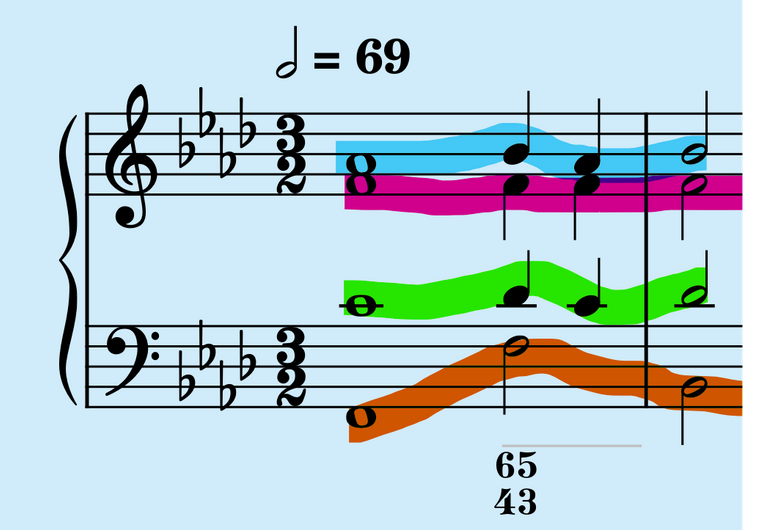

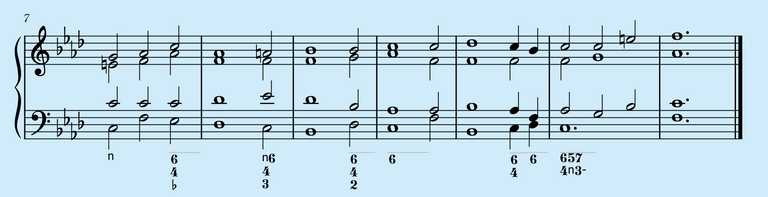

Here's an example from an old book way back in 1909 of exercises for students, by James Lyon:

From these few bars of music, a whole beautiful piece can be created with close to zero creativity on my part.

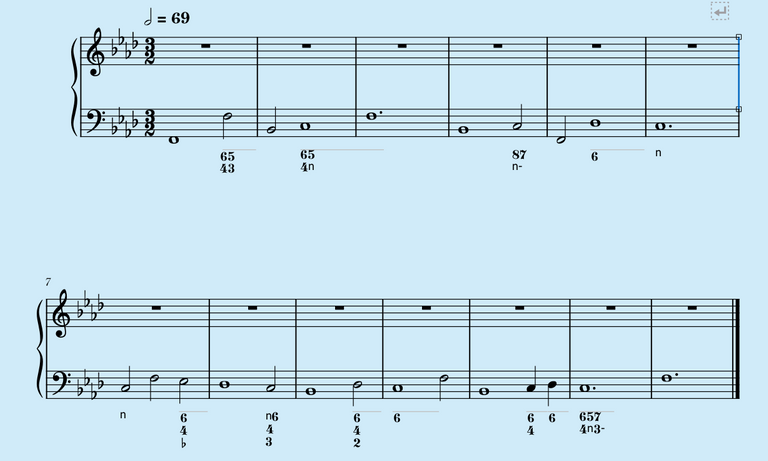

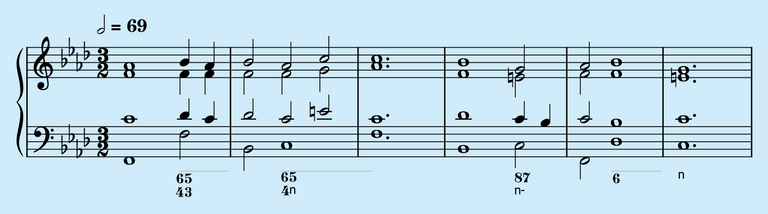

I went ahead and copied that down into notation software:

So what do those numbers even mean?

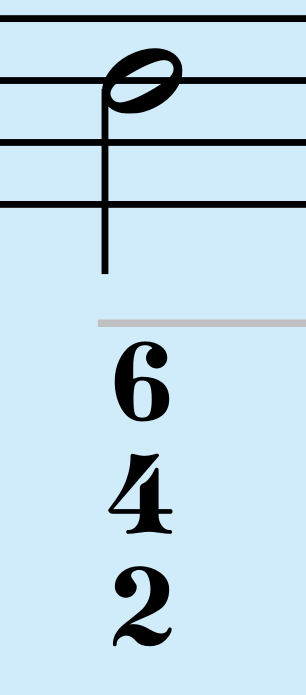

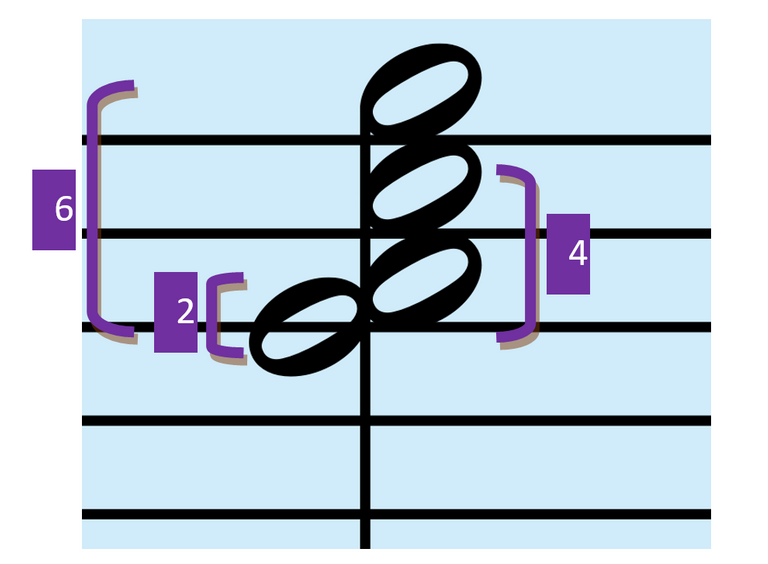

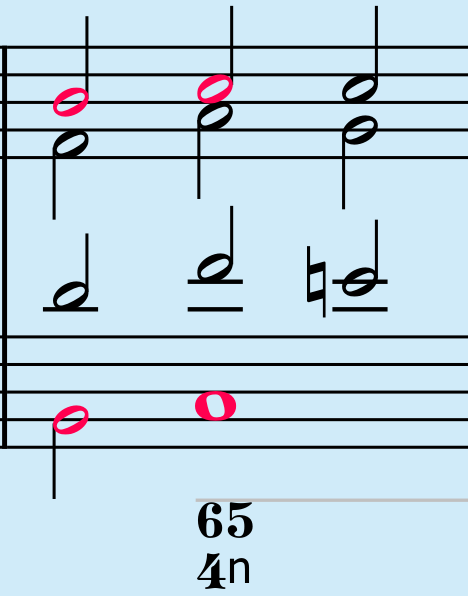

Doing my best to avoid bloated musical terms and such, they basically describe the relationship between each note in a chord, specifically the arrangement from bottom to top. For example, when you see this:

It basically means you start with the note provided, considered as 1, then you go up one step higher '2', then two more steps higher to 4, and two more after that, '6'. You can consider this as 'Do, Re, Fa, La' if you know your Do re mi's. In simple chord block form that would look like this:

The only thing left to do is to spread that out over four separate voices, as if you were writing for a choir.

Unfortunately it's not that simple really. In order to make the music actually sound nice, composers over centuries worked out a bunch of rules that meant certain intervals between notes weren't over-done, or large leaps in melody weren't too jarring. But at the same time as being conservative in this way, the rules also assured the melodies in each voice remained interesting, which is the whole point, really.

Though taught as a musical exercise in AP Theory Curriculum, it's always acknowledged that these rules only apply to this style in particular we call counterpoint, and that a lot of great music - indeed most of it - comes from actively breaking these rules. This is not the only road to good music. It's just a way to learn and improve one's understanding of the relationship between various notes and harmony nowadays.

That being said, they do tend to sound pretty darn sweet! So, if I can realize this figured bass for you, the end result should sound rather pleasant and quintessentially classical, the likes you might get from Bach or something.

Let's do this!

Back to Bass-ics

Now I'm not going to spend my entire free time toiling over every one of the hundreds of rules for this piece, but I will pay attention to some of the BIG nono's. These are called 'parallel 5ths and octaves'. Basically, a distance of a 5th (from Do to So) and an 8th, shouldn't move in a parallel direction one after the other. This is because they are very overwhelming, a bit too strong for the soft ears of our predecessors.

Later on, this was deliberately used as a compositional tool, famously with Debussy who used consecutive motion like this all the time. And, of course, it sounds great.

In modern music, this is now just called 'power chords' and supplies Rock music with about 90% of its sound.

Ok so let's get into it.

The first note has no number symbols. This just means the 'standard' order of 1-3-5 should be used, or 'Do-Mi-So'. In practice it really just means the note provided is Do, and you fill the rest in with the other notes.

Here's how I started:

It's important to keep in mind the 'interest' level of each individual line. You might notice how the lower line in the top half is all the same note. This is considered pretty boring and not generally encouraged for more than a couple of notes, but I'm keeping it because F*** the rules.

Later on, you often find you get trapped into a situation where motion is too minimal and you regret your earlier choices. Even the starting 4 notes have a certain influence on the entire outcome of the piece, so it's not uncommon to become unsatisfied halfway through, requiring you to scrub the whole thing and start over. Hopefully not this time round!

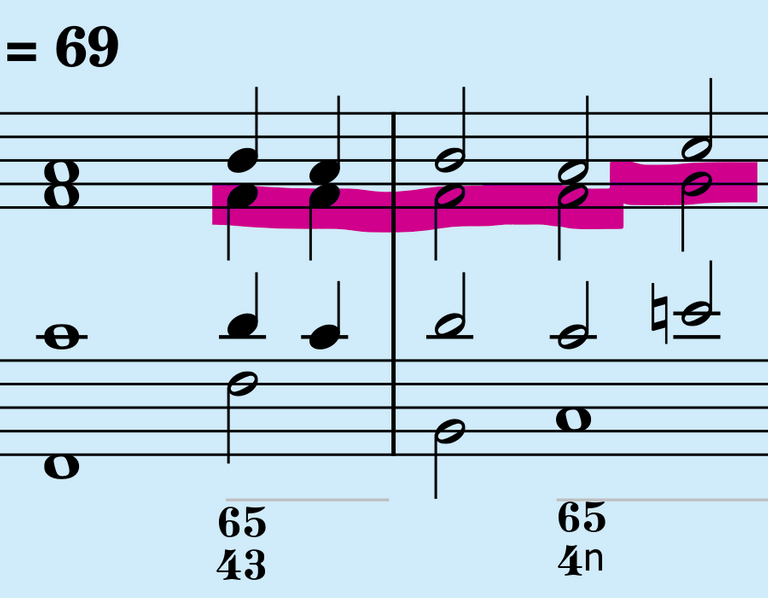

Shortly after, I come across a barrier where I'm pressured to use a parallel octave mentioned above. These can be quite well hidden:

Both the bottom (bass) and top (soprano) voices are singing identical notes as each other twice in a row.

WRONG!!!

This is where you have to jiggle things around to avoid such criminal acts. My new solution demonstrates my earlier problem, setting oneself up for boring, one-note lines for extended durations, but I finally break out towards the end.

Getting the vibe

It doesn't take long before you start to hear the inevitable intention of the piece. This is quite a dark, melancholy piece, almost like a funeral!

With some of these rules taken into consideration, others not so much, here is my end result for the evening:

Take a listen and see what you think! (forgive the low quality screen-capture sound... Not exactly a professional production here.