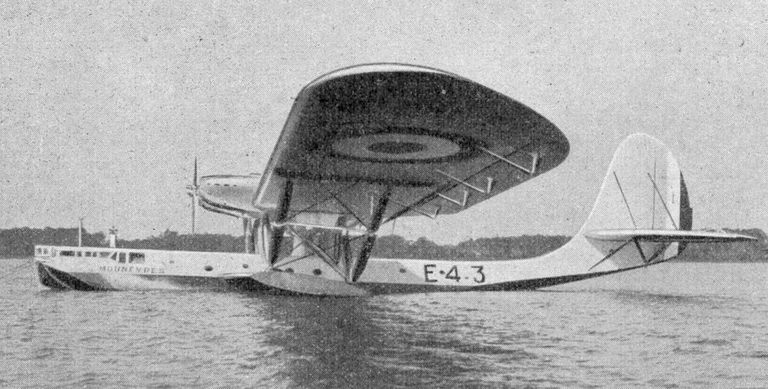

(A Latécoère 302 hydroplane. Source: link)

Reading on in "Terre des Hommes" (here is part I if you missed it), I keep being impressed by Saint-Exupéry's description of our relationship to artefacts.

C'est avec l'eau, c'est avec l'air que le pilote qui décolle entre en contact. Lorsque les moteurs sont lancés, lorsque l'appareil déjà creuse la mer, contre un clapotis dur la coque sonne comme un gong, et l'homme peut suivre ce travail à l'ébranlement de ses reins. Il sent l'hydravion, seconde par seconde, à mesure qu'il gagne sa vitesse, se charger de pouvoir. Il sent se préparer dans ces quinze tonnes de matières, cette maturité qui permet le vol. Le pilote ferme les mains sur les commandes et, peu à peu, dans ses paumes creuses, il reçoit ce pouvoir comme un don. Les organes de métal des commandes, à mesure que ce don lui est accordé, se font les messagers de sa puissance. Quand elle est mûre, d'un mouvement plus souple que celui de cueillir, le pilote sépare l'avion d'avec les eaux, et l'établit dans les airs.

Here is my attempt at a (less poetic) translation:

"It is with the water and the air that the pilot connects while taking off. When the engines are started, and the hydroplane is dragging through the water, the hull echoes the tapping waves like a gong, and the man senses this work by the vibrations in his lower back. He feels the hydroplane get charged with power, second by second, as it gains speed. He feels these 15 tons of matter acquire the readiness for flight. The pilot puts his hands on the controls, and little by little, in his palms, receives this power like a gift. The metallic organs that are the controls, inasmuch as he possesses this skill, become the messengers of his will. When it is ripe, with a gesture that is more fluid than that of picking a fruit, the pilot separates the plane from the water, and establishes it in the air."

This goes back to a previous theme, that a good artefact will tend to become transparent, a kind of minimal mediator between us and our purpose. The pilot cares about going from the water to the air. He can appreciate the abilities conferred to him by the plane, but when it comes to the actual act of flying, he is not thinking about the plane but about his purpose.

Saint-Exupéry even attributes organic qualities to the plane, both sensory and motor. The hull acts like an extension of the ear, allowing the pilot to sense the water resistance and the buildup of strength. The plane's controls are described almost as extensions of human limbs, turning our arms into wings.

Interestingly, he says that the gesture is more fluid than that of picking a fruit, which suggests that this machine has grown closer to man than even our ancestral hunter-gatherer instincts. This is in line with his belief that our past way of life is not necessarily better suited to our nature than the present one (cf. part I).

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://www.etudes-litteraires.com/forum/topic54528-antoine-de-saintexupery-terre-des-hommes-quimporte-guillaumet-si-tes-journees.html