WHERE ARE THE AMAZON ROBOTS? (Part two)

In part one of this series, it was noted that anecdotes about working in Amazon warehouses tended not to mention robots. The essay went on to show how there are robots in those warehouses, in a manner of speaking. Human packers and pickers are effectively turned into robots through production-line techniques and handheld devices that track their every movement. Will such fleshy robots ever be comprehensively replaced by what we would regard as the ‘real thing’?

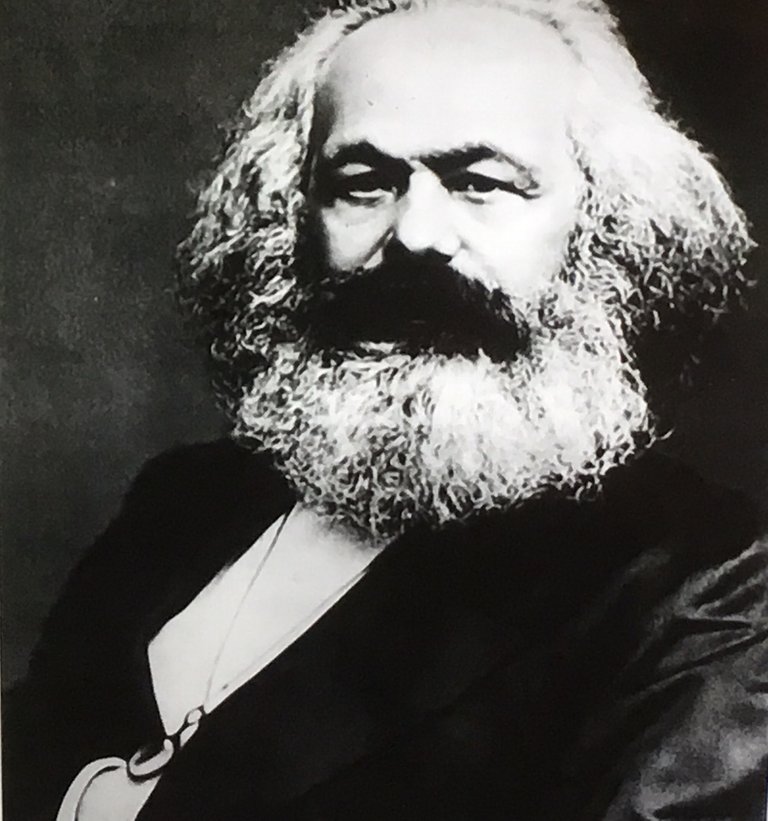

Many an economist would once have thought so. Back in the 19th century, Karl Marx identified what he thought would result in the rise and inevitable fall of Capitalism. To Marx, history was all about class struggle driven by the opposing desires of different groups of people. In Marx’s day (and ours too) those classes were, roughly speaking, ‘owners’ (bosses, in other words) and ‘labourers’ (employees). These classes were opposed in that employees would rather wages rose, while bosses would prefer them to fall, because the cheaper labour is the more profit you can squeeze from a workforce. However, there is always a limit to how much work you can get out of a human being, and how cheap that labour can be, because there’s only so much work humans can do before they absolutely refuse to do any more. So Marx believed that wages would tend toward an absolute minimum wage.

(Image from wikimedia commons)

Marx also predicted that, because bosses always want more profit and human capacity to work is limited, they would be compelled to research and develop means of extending human ability, through things like mechanisation. He never mentioned robots because the concept was not really around in his day, but you can bet that if the term had been familiar, Marx would have predicted that businesses would tend towards a state of full automation as employees get replaced by robots that can outperform them.

Marx saw in this pursuit of more profit achieved through lowering costs the ultimate downfall of capitalism. You see, capitalists sell things to consumers, and consumers need money to buy stuff in a capitalist market, and they get money by earning wages, which the capitalists are striving to reduce to zero through innovation. Robots might work for no wages but they don’t buy anything. If robots don’t buy anything and most people can’t buy anything because their job has been replaced by robots, capitalism has brought about its own destruction, all caused by owners forgetting where, ultimately, their wealth comes from.

In the hundred or so years since Marx wrote ‘Das Kapital’, there have been debates over how accurate his analysis of production and capitalism was. Plenty of people see Marx as something of a failure. They point out that Marx reckoned the working classes were fated never to be lifted from poverty. Should wages ever rise, Marx thought that this would eat into profit making more and more businesses not economically viable as the wage-rate increased. This would lead to more businesses going bust, which would lead to more unemployed people lowering the cost of their labour in order to represent better value to prospective employers, and those in jobs feeling the pressure to lower the cost of their labour in order to remain in their jobs.

He also predicted that the very richest countries who had progressed capitalism to its peak efficiency would have created so much wealth inequality that the great mass of impoverished working-classes would revolt and bring down the system.

But as the 20th century unfolded neither of those predictions came true. The Marxist revolution did not originate in the world’s richest capitalist nations, but rather in Russia, which at the time had barely begun to industrialise. Also, far from the working class never being able to escape from poverty because of capitalism, in fact standards of living in capitalist countries rose, and the percentage of those in absolute poverty has fallen. Rising standards of living and falling percentages of those deemed to be in absolute poverty has led many people to believe that, far from revolting against capitalism, we should grant capitalists more freedom to do their thing, since nothing else has done as much to improve lives.

Now, what about the prediction that capitalism’s pursuit of more profit would force it to replace people with robots? Could that also turn out to be a failed prediction? This would not have been what most economists predicted. Great minds like Keynes saw increases in productivity and innovation and expected that, by the 21st century, the main problem would be how societies formerly based on work and scarcity would adjust to the new reality of leisure and abundance. Such expectations and fears persist to this day, despite the fact that we’re well into the 21st century and employment still very much depends on people. “What will people do when robots have taken their jobs” gets asked a lot.

But maybe capitalism won’t ever pursue automation to a level where capitalism itself is threatened? Maybe it is willing to increase prosperity only so far?

What I am suggesting is that capitalism’s ‘willingness’ to innovate toward ultimate prosperity is limited. It is willing to reduce levels of absolute poverty. Wherever there are desperate people, businesses will move in and set up sweatshops. Or, if immigration laws permit, people will be shipped over from poorer countries to do hard work for low pay in fields, warehouses and homes (think of all the immigrants working on farms, in Amazon warehouses and as domestic servants).

Capitalism is also willing to fill our lives with more and more consumer luxuries if, by doing so, a fair few of us are likely to be lured into debt and therefore obliged to submit to wage labour in order to reduce our debt levels. Hence, we got credit cards, mobile payments, one-click online shopping...and big bills we work to pay off, leading to more compensatory consumerism as we buy yet more stuff as a way of justifying sacrificing the better part of our lives in jobs most of us don’t particularly enjoy.

But what capitalism won’t do is to innovate and automate to the point where it becomes obvious that abundance is now so readily available that nobody needs to submit to labour for a wage anymore. A sign that my prediction is coming true would be if progress is seen to head upwards towards more automation, but then veer away as the drive to save capitalism from extinction sees us reducing innovation so as to perpetuate the status-quo.

I think a case can be made that something has gone wrong with innovation and progress. If we look back over the 19th and early 20th century, we see the flowering of major scientific theories. The theory of evolution by natural selection; the theory of relativity; the Big Bang; quantum physics. We also had major technological development and revolutions. The industrial revolution, railroads, aviation, electrification, computing, and at the end of the 20th century, the Web and the digital revolution.

Now, the Web is pretty cool. But I suspect that 19th/20th century time travellers would be disappointed to learn that this was the pinnacle of technology in our day and age. I mean, really, what is the Web from the consumer’s perspective? It’s a platform for sharing messages. It’s a way of consuming media. It’s a kind of catalogue that makes buying stuff more convenient. I imagine a conversation between a time traveller from the 1960s and a Web user of today would go something like this:

“So I have heard of this thing called ‘The Internet’. Could you explain what that is?”.

“I’ll try. I guess the best way to explain it to you would be to say it’s a sort of combination of library, postal service, TV broadcaster and radio station, and a mail-order catalogue, all accessible by this thing here called a ‘smartphone’”.

“Smartphone? Ah! Machines that can think!”.

Then it would dawn on the traveller that, actually, we still don’t have machines that think or robots doing jobs, at least not on anything other than a very minimal level. He would compare the progress of the past, things like going from horse-drawn carriages to travelling into space at supersonic speeds, and compare that to now, where progress consists of minor alterations of the same product (the new iPhone 11!) and rumours of technology that always seems to be ‘just on the horizon’ (“I hear driverless cars are on the way”).

Suitably disappointed, our traveller would want an explanation for why a ‘Star Trek-style’ future failed to materialise in the 21st century. He would discover that Amazon still employs cheap human labour to do what could be automated, and he would learn about jobs that had been automated in the past but which were now done by hand. Think of automated car washes, which in some cases were shut down because it’s cheaper to pay wages to wash cars manually than to maintain an automated car-washing facility. Or at least it is if wages fall far enough.

Wondering what led to such a drop in wages would lead our traveller to transformations that began some time after the 70s. Up until then, productivity and overall prosperity had more or less gone hand-in hand, as successful businesses made more profit and this was reflected in improving working conditions and wages for the workforce. This was not achieved by capitalism alone. Instead, it was through a combination of capitalism organising people and money in order to unlock more and more potential abundance, and socialism putting pressure on the capitalists to spread that wealth more widely, that led to rising prosperity. Workers organised themselves into unions, and Left-wing governments gained enough support to become an influential voice. Innovation and prosperity came about because of high taxes, since Big Business figured it was better to divert some capital toward higher wages for staff, or to pour it into R+D, rather than see the taxman make off with it.

By the end of the 70s, though, this concept of workplaces devoted to looking after all stakeholders began to change. Popular opinion increasingly viewed Blue-chip companies as too monopolistic and their workforce too entitled. Right-wing politicians who abandoned Keynesianism and its emphasis on the working classes/ consumer as the source of profit and adopted more laissez-faire capitalism operating under monetarist assumptions gained power. Tax rates for the wealthy were slashed and executive pay was tied to share price performance. It was thought that lower taxes and executive pay tied to the bottom line would result in even more innovation and it did, in a way. But maybe not in a way that many ordinary folk who voted for Right-wing governments intended. You see, it led to financialisation, and a new breed of ‘active investors’ chasing ways of increasing the paper value of businesses without adding a penny to the nation’s production. This was achieved through Wall Street innovations like ‘high yield’ bonds (aka junk bonds) that made it possible to borrow money for high-risk investments, with the high rates of interest banks insisted on paid back by laying off huge numbers of workers and destroying whole communities, all so that short-term boosts profits could be achieved and more junk bonds could be bought, and the game of layoffs, mergers-and-acquisitions, and rising levels of executive pay alongside deteriorating working conditions for everyone else could continue.

Also, globalisation opened capitalism up to huge pools of cheap labour. Businesses no longer innovated quite as much in terms of seeking physical innovations partly because the emphasis on short-term profits meant companies wanted quick returns, which was why we now get endless iterations of the same damn product rather than really wow techs sprung from blue-sky thinking, but also because with such ready access to exploitable labour and years of Right-Wing propaganda eroding people’s faith in Left-wing policies and diminishing the power of collective bargaining among the working classes, businesses had no need to R+D robots when a combination of worker exploitation amongst the most vulnerable groups and financial innovations like credit cards etc could keep consumerism going in ways that would never threaten the fundamentals of capitalism itself.

You see, capitalism is ultimately based on competition under conditions of scarcity and most people today would see the essence of capitalism as being all about creating businesses that employ people to do jobs in competition against other businesses. Some measure of progress towards more prosperity is permissible but not too much. This is because generations of people have lived under this shadow of the boss and this has led to the prevailing belief that if you are not prepared to slave away in a job you don’t particularly enjoy, you don’t deserve to share in collectively-produced wealth. Innovations that perpetuate this cycle of wage slavery, such as workfare programs dragooning the financially insecure into employment, and cheap credit luring more and more into conditions of financial insecurity, are allowed. But radical innovations that could push the arrow of progress beyond the point where hardly anybody needs to submit to wage labour anymore? We don’t want that.

Well, there’s lots of claims being made here. We’ll get into the evidence supporting all this in the next episode.

References

‘Das Kapital’ by Karl Marx

‘The Utopia Of Rules’ by David Graeber