A question needled its way into my head as I ate Easter dinner at my parent's house yesterday. My family displays a wide, rambling, and diverse level of piety. There's my mother who is the church-on-Sunday type, my father who pulled me aside after my confirmation and said, "You know, this is all bullshit", and my uncle, my mother's brother, who is the Christmas Eve-guitar-mass, Pre-Cana-organizing, I-love-Jesus-crewel-work guy. I love my uncle despite our ideological differences, and he usually accepts my atheism by acting like I'm kidding. For my part, I avoid discussing religion with him because doing so is like an unsharpened pencil (it's pointless). The tenuous thread that holds our relationship together is carefully woven denial: he won't accept that I can be serious about my notions of a Godless universe, and I try to forget that an ordinarily rational man believes in guardian angels. But every so often, when our meme-fueled genes or gene-fueled memes get the better of us, we forget about our unspoken agreement and wander into religious terriority...like yesterday.

I forget exactly how it started, so I'll do the resplendently childish thing and blame him. I'm sure it was him because I certainly had nothing to gain from what amounted to the loss of a perfectly good hour of my life arguing about things neither of us can prove. But it was he who drew first blood, literally, with talk about the blood of Christ and whether or not it actually becomes real blood. Like anyone calling himself a Catholic, he does. He asked me if I do, to which I reluctantly said no, which led to him asking me if I believe Jesus is divine, to which I even more reluctantly said no, to which he pronounced his magnum opus:

Let me tell you a story, he said. It bears mentioning that my uncle is a remarkably good salesman. It's a story about a boy born into poverty. He has no schooling, as his father is a carpenter. There is no reason on earth that anyone should listen to anything he has to say about scripture or God, but they do. He starts a ministry, and just as it starts to become popular, he's brutally murdered by the Romans...yet, over 2000 years after his death, we mark the calendar with his birth. He stopped and took a swig of Sambuca, avoiding the espresso bean along for the ride. And now you're going to tell me that he isn't the son of God?

Of all of the evidence I'd been shown promoting the divinity of Jesus, I had not, until that moment, heard that his popularity was one of them. If that's true, then Todd Rodgers, the quarterback of my high school football team, should also be able to walk on water, which he did unsuccessfully try one night after consuming a Jack Daniels beer bong--the stuff of legend. My uncle's argument is absurd, an ex-post facto claim, but one that fits his chosen profession. This is what salesmen do. They tell us something is great because everyone's using it. In the world of sales, popularity imbues the sales object with an other-worldly quality: buy this product and it will solve all of your problems.

But as ridiculous as I thought my uncle's argument was, a legitimate question emerged. Why is Jesus so popular? How did a religion created by and for the poor rise to the greatest heights in the richest and most powerful nations on earth?

Christianity Off to a Slow Start

Nearly three hundred years after Jesus' death, the community of Christians was relatively small [1]. Yes, Christians were persecuted, but no more than other fringe groups. There were the high profile mass persecutions by Nero and Domitian, but other than that, Christians weren't persecuted so much because they were Christian as because they would not adhere to local customs [2]. A more pedestrian but realistic version of Christian persecution probably went something like this.

Our crops are dying. Why hasn't it rained?

I don't know, but those weirdos over there won't pray to our god.

They won't? Well, kill them. Maybe then it'll rain.

Sounds good.

Christians lived in quiet obscurity with occasional periods of mass killings until the Roman Emperor Constantine decided they had a greater purpose to serve. Constantine, despite being venerated as a saint, was a tyrant and a mass murderer just like every other Roman emperor. So why would a tyrant and a murderer be interested in Christianity, a religion that espouses peace and love?

Constantine the Great(-at-Murder)

One thing we know definitely about Constantine is that he united the eastern and western empires of Rome [3]. This was an incredibly difficult feat, and must have required much of his time and energy over a period of many years. To achieve something of such magnitude requires a dedication bordering upon obsession, and single-mindedness of purpose and tremendous discipline. According to the chronicler Eusebius of Caesarea, it also required divine intervention.

Eusebius recounts how Constantine had a vision of the cross just prior to the Battle of the Milvian Bridge where he faced and defeated his rival, Maxentius, to become the sole ruler of the Roman Empire [4]. He had his soldiers wear the sign of the cross on their shields, and as a result, and in reverence to the vision and the accompanying dream in which Constantine spoke directly to Jesus, victory was his. The problem with visions is that no one else sees them, and they are impossible to verify. Constantine’s eyes may have been playing tricks on him, or it may have been the onset of fatigue, or a reflection off of one of his general’s shields. Or, he may have made the whole thing up.

Setting the vision aside, why else would Constantine be interested in Christianity? Was it the philosophy of forgiveness and loving thy neighbor? Doubtful, since Constantine had his own son and wife executed. Was it the anti-violence message? Constantine used warfare and murder as a means to advance his political agenda, a sort of Michael Corleone on bath salts. What was it then?

Consider the following hypothesized piece of dialogue between Constantine and one of his advisors.

CONSTANTINE: I have to find a way to unite the Empire.

ADVISOR: Why not try using religion?

CONSTANTINE: How? There are so many different gods, I can’t manage that.

ADIVSOR: Well, how about the god of the Jews? They have only one.

CONSTANTINE: Ah, the Jews are a pain in my ass. They’re too militant, always planning an uprising and then I have to go in and slaughter them.

ADIVSOR: Why are you knocking Rome's favorite hobby?

CONSTANTINE: Forget the Jews.

ADIVSOR: Well, how about the Christians?

CONSTANTINE: You mean that little group of hippies?

ADIVSOR: Yes.

CONSTANTINE: I don’t know much about them. What are they like?

ADIVSOR: They have only one God, and it’s the same one that the Jews worship.

CONSTANTINE: You’re about to get two thumbs way down.

ADIVSOR: Christians are peaceful. They are against violence.

CONSTANTINE: Yeah?

ADIVSOR: Yes, and they don’t mind being poor.

CONSTANTINE: (Pause) Go on.

ADIVSOR: In fact, they like being poor because it means they will receive a greater reward in the next life.

CONSTANTINE: So they live their lives for when they’re dead?

ADIVSOR: Yes, and I’m told their founder, who we brutally executed hundreds of years ago for being insolent, taught that if someone strikes them across their cheek, that they should offer up the other one as well. And if someone steals their coat, they should offer their cloak too.

CONSTANTINE: So let me get this straight. If I abuse them, they’ll not only forgive me, but request more abuse, and they don’t care about money or how miserable they are, because they’re expecting reward in the afterlife?

ADIVSOR: Pretty much. (Pause) Constantine what’s wrong?

CONSTANTINE: I’m…having a vision.

ADIVSOR: A vision of what?

CONSTANTINE: A vision of...what’s their symbol?

ADIVSOR: A cross.

CONSTANTINE: I’m seeing a vision of a cross.

Constantine may have had a vision, but perhaps it wasn't of the cross. Maybe it was of the Roman equivalent of the dollar sign. Cha-ching!

References

The Spread of Christianity in the First Four Centuries (Columbia Studies in the Classical Tradition.

Bart D. Ehrman, A Brief Introduction to the New Testament (Oxford University Press 2004 ISBN 978-0-19-536934-2), pp. 313–314.

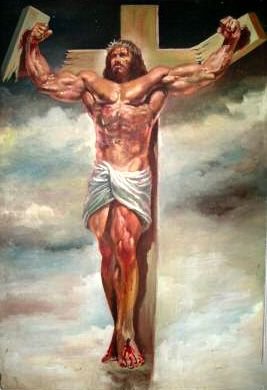

The picture is just as funny as the article. Good stuff on Constantine, but to get really behind your theory we'd want to see a reasonable counter-argument on Constantine's "greatness". Not from a religious-freak tho, we'd want to hear a credible historian's take on why Constantine wasn't a bloody murderous mess of a man, just to compare notes. But it's very interesting from the standpoint that Constantine did the most to solidify and perhaps alter (or even make up) the entire story of Jesus. It's always fun to look at the pagan religious and find the myriad of similarities in the stories. For instance "Rah" is the sun, almost literally, and in Christianity it's the "son" who is God on earth. That's loose affiliation. But where it gets strong is the Heaven and Hell concept which of course was pushed heavily by John the Baptist's inherited Galilean ministry of Jesus. Hades lives literally in the hot magma under the Earth's crust, while Zeus lives far above the clouds in the heavens, with an address right near Yahweh's home.

Also interesting from a physics standpoint, gravitational pull causes Hades, and "God" is outward, one must overcome gravity to reach Heaven. It's like our race has ALWAYS known that we must soar above our rock, and not get nailed down to it or it all ends in fire which kills from within. And is not Einstein a prophet, the king of gravity?

But we're a sports jock mentality, so we're only interested in any of this from the standpoint that Jordan Spieth and Zach Johnson wear their religions on their Under Armour sleeves. And it works. So maybe Constantine knew something about overcoming adversity on the field of battle (mentally at least). .... or whatever you wanna tell yourself!

Thanks for the inspiration for a future article regarding religion and sports/athletes.

And why is this post so unpopular? Hmmm.

We found Jesus in our cumstain.

How was he? A little flakey?