Glaciers around the world are retreating rapidly, and the scale of loss we’re facing is far greater than what’s visible today. A major international study, using simulations from eight glacier models and covering long-term projections, has concluded that nearly 40% of the glacier mass outside of Greenland and Antarctica is essentially already committed to melting—even if the planet’s average temperature were to stop rising immediately. This would raise global sea levels by more than 10 centimeters over the coming centuries.

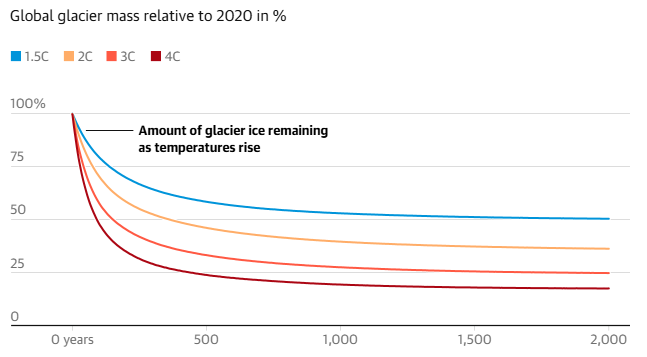

The research, which includes contributions from over 20 scientists across 10 nations, emphasizes how glacier systems respond slowly over time. While many climate models typically project changes up to the year 2100, this study extended much further into the future, showing that ice loss continues well beyond this century due to the inertia built into glacier systems. This lag in glacier response means today’s warming will be felt for generations, as ice continues to melt and retreat to higher altitudes, eventually settling at a new equilibrium.

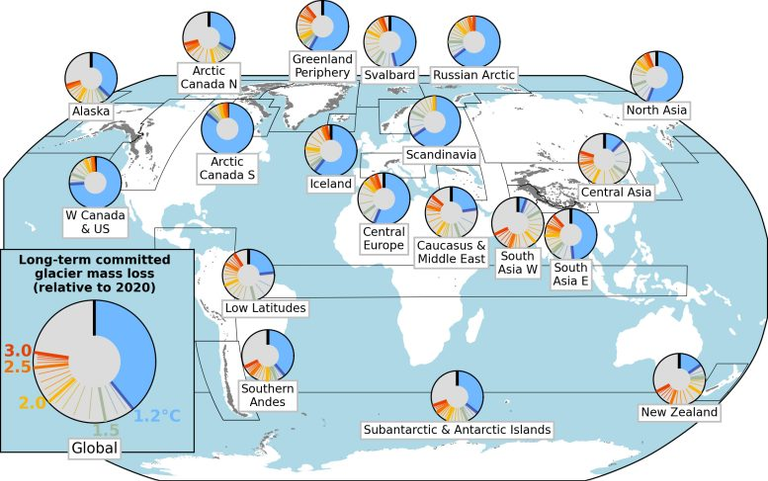

One of the clearest takeaways is how temperature thresholds relate directly to glacier loss. If global temperatures rise by 2.7°C—the path we're currently on under present climate policies—up to 76% of global glacier mass could vanish over time. In contrast, holding warming to 1.5°C could preserve more than half of glacier ice, nearly double what would survive under the higher warming scenario. These findings reveal the stakes: every tenth of a degree makes a measurable difference. For each additional 0.1°C of warming between 1.5°C and 3.0°C, the world risks losing approximately 2% more of its glacier mass.

The consequences of losing glaciers extend far beyond aesthetics or tourism. Glaciers are crucial freshwater sources for millions of people, feeding rivers that support agriculture, drinking water supplies, and hydropower generation. Their disappearance also increases the risk of natural disasters like landslides and glacier lake outburst floods. As these frozen reservoirs shrink, regions dependent on meltwater will face mounting challenges, potentially crossing a threshold where adaptation is no longer feasible.

According to scientists involved in the study, such as Harry Zekollari and Lilian Schuster, the future of glaciers hinges on today’s climate decisions. Zekollari, a researcher associated with institutions in Belgium and Switzerland, underscores that the long-term loss is not speculative—it’s based on physical models run across multiple scenarios. While the numbers might seem daunting, the message is one of cautious hope: decisive climate action can still make a meaningful difference.

This research aligns with the goals of the United Nations’ International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation, highlighting the urgency of international cooperation. Countries that signed the 2015 Paris Agreement committed to keeping global warming well below 2°C and ideally under 1.5°C. Yet, current trajectories suggest a rise of up to 2.9°C by the end of the century, falling short of those commitments. The difference between a 1.5°C and a 2.7°C rise is not abstract—it’s the difference between a world where glacial melt is manageable and one where the consequences are overwhelming.

Although the study provides a sobering view of what's already set in motion, it also reinforces a critical scientific point: the future is not predetermined. The models used in the research span a range of outcomes—from 15% to 55% mass loss under current conditions—showing that while uncertainty exists, the direction of change is consistent across all simulations. As glaciologist Guðfinna Aðalgeirsdóttir notes, no matter which model you consider, increased warming leads to more glacier loss. This consistency strengthens the call for immediate, sustained climate action.

Regionally, the risks are not evenly distributed. Glaciers in parts of North America, northern Europe, and the Arctic are particularly vulnerable due to their exposure and sensitivity to warming. Local communities in these areas may feel the impacts of glacier loss sooner and more intensely, making regional adaptation and policy support equally critical.

Ultimately, the study’s central message is both urgent and empowering: we are not powerless. The degree of warming in the coming decades will determine how much glacier ice survives into the future. With each degree—and indeed, each fraction of a degree—of restraint, we can protect not just ice, but the ecosystems, economies, and communities that depend on it.

This post has been shared on Reddit by @tsnaks through the HivePosh initiative.