of the moment. There is no why.

—Kurt Vonnegut

There are no rules to mental illness and one patient is totally unlike another.

My advice to young interns is always the same—toss out the DSM because there are as many variations as there are patients.

Take Nate Hanley for instance. Last night he refused to cooperate because the on-duty psychiatrist changed his prescription.

Security was called and he’s now in restraints in an isolation room, while Maynard Reese, another patient, is standing outside his door taunting him.

“Get back to the patients’ lounge, Maynard,” I tell him. He blinks at me, but quickly complies. He knows the game—act out and your privileges are withdrawn.

I peek in at Nate, now subdued and injected with Thorazine. I chuckle. Maynard had nothing to fear—Nate’s experienced a form of chemical lobotomy and won’t be punching anybody today.

I glance around the new facility with its brightly painted walls and huge windows—the community finally got it right and spent some money on mental health for a change.

It’s four o’clock and already the December day’s drawing to a close. Soon the beds will be filled with depressed patients with seasonal affective disorder and others who can’t cope with being bullied into Christmas cheer.

A lady with schizophrenia is looking out the window calling to a young man with bipolar disorder—“Come here, Jim—take a look at the plywood tree outside.”

“Naw, Edna—trees are cottonwoods, oaks, or elms—you can’t have a plywood tree—it’s just sawdust and wood scraps glued together.”

I go over, stand beside her and peer out the window. She’s looking at a cutout plywood Christmas tree on the East wing roof. I smile to myself—even reasonableness in a psych ward becomes transmuted into something else.

Karen Olmstead, the heavyweight night nurse, has just come on duty and is rounding up patients to get their meds.

They call her Klink—probably a reference to the Colonel in Hogan’s Heroes who ran the Nazi concentration camp. Pretty perceptive, I think.

Klink spots me. “Doctor Wallace, can you look in on Amber Taylor? —She’s the new patient I told you about who thinks she’s a time traveler.”

I sigh. It’s been a long day and tomorrow will be even longer as I see my private practice patients.

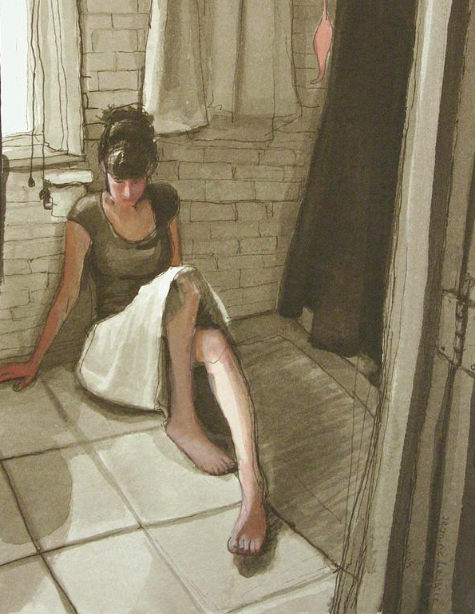

I wander back to Room 324 and spot her name tag on the door. I knock softly and poke in my head. She’s sitting by the window watching the blue tree shadows in the snowy ravine outside.

“Amber?”

She looks up and smiles. “Pretty isn’t it? I like snow—always have.”

I pick up a chair, drag it to the window and sit down beside her.

“Aren’t you cold?” I ask, noting the window slid open the few inches allowed for fresh air and no socks on her feet.

“No. I grew up here and got used to freezing weather. Sometimes those Alberta clippers pick up the snow and you feel your face is being sand-blasted—or ice-blasted, as the case might be.”

I liked her. She had bright eyes and a warm smile. If I hadn’t seen her chart, I’d think her totally normal. The notation reads bipolar I disorder—psychosis, delusional thinking, hallucinations and disordered thinking. It’s not my diagnosis, but that’s why she’s in here.

“Do you know why you’re in here, Amber?”

Her huge eyes grow sad. “I was brought here on a form—the policemen said I wasn’t arrested, but apprehended. They put handcuffs on me.”

“And why did they do that?”

“Said they had no alternative—said I was non-compliant because I told them I wasn’t crazy or a danger to myself.”

“Why did they think you were crazy?”

“I guess because I walked into the Empire Room and kinda had a meltdown.”

I was intrigued. “Why was that?”

“Because everything was changed. It used to have a big sculpted ceiling, and plush green drapes with gold tassels and about a hundred tables covered with white table cloths and it was all gone—all changed—overnight!”

“You worked there?”

She nods, “As a waitress.”

She begins folding and unfolding the hem of her dress.

“ I asked for Eddie my boss and they said he didn’t work there—never did. I guess I got pretty upset—okay, maybe hysterical. Anyway, that’s when they called the police and they finally brought me here.”

“Where is this Empire Room?”

“It’s in the Palmer House Hotel downtown—Oh, why doesn’t anybody believe me?”

“I guess because the Empire Room is no longer there, Amber. It was there in the 1940’s, but not now.”

She sighs. “Okay, okay—I believe you. Just tell me how to get back.”

“Get back where?”

“Get back to my life—to the 1940’s. I don’t belong here.”

“How did you get here?”

“I don’t know. I went to bed, had a funny dream and woke up walking downtown. I spotted the Palmer House, went in and—well, here I am.”

I tried a different tack. “Where did you go to high school?”

“South Shore, here in Chicago.”

“When did you graduate?”

“1945.”

“And you’re convinced you went to sleep one night in 1945 and woke up here seventy years later?”

She shrugged. “I guess so—I don’t have any other explanation.”

It was close to five and I had a dinner date with Tara, my wife.

I made a note to check the details of Amber’s story and see if she had any relatives living in the area. I wanted to interview her further, but the time was getting late and I had to go.

“I’ll be in to see you tomorrow, Amber and we’ll check the details of your story. Don’t worry—we’ll get to the bottom of this.”

“I hope so,” she replied. She looked so lost and forlorn, I wanted to stay and comfort her, but as I said, I had made the date with Tara and didn’t want to disappoint her.

I wrote a scrip for a mild sedative for Amber and benzodiazepine for her bedtime.

I don' t know why, but I half-believed her—as improbable as her story sounded, everything about her from her hairstyle to dress shouted 1940's.

And the the truth is, she seemed completely sane.

Thank you!

https://bsky.app/profile/did:plc:re6vo5ekuz46cmjrwqjyet53/post/3llw2ahxpvk2i

https://bsky.app/profile/did:plc:re6vo5ekuz46cmjrwqjyet53/post/3llw2ahxpvk2i

The rewards earned on this comment will go to the author of the blog post.