With regard to the difficult events and situations presented in recent times in Latin America and other parts of the world, it would be well to revisit the work of certain leading authors of contemporary Western thought. One of them for me is Elías Canetti, thinker and writer (essayist and narrator), born in Bulgaria in 1905 and died in Switzerland in 1994.

Ever since I began reading it years ago, I have always imagined him gravely dressed in his dark coat, clothed in his Kafkaesque mist and little speech, elusive and overwhelmed by his Jewish ancestral memory. Canetti, who in 1981 received the Nobel Prize for Literature, for many long years had forged a writing in which density and lucidity became the narrative of thought, or where narration gave way to memorable and forewarned reflection. An autobiographical thread, almost proustian, warped his writing, be it fiction, essay or research.

The innocence and cruelty of childhood, the threatening presence of death, the "love and terror of words" (to say it with the phrase of the Venezuelan Briceño Guerrero), the dispersed voices of the collective conscience configured the ferment and breath of works such as The voices of Marrakesh (1968) or The absolved language (1977), the latter form initiates his autobiography that consists of four volumes. Added to this is the testimony of the suffering he experienced as if in his own flesh, witnessing the tragedies of this century - the "great" tragedies of history, such as the two world wars and the holocausts of humanity generated by the aberrant products of humanity itself (Nazism and Stalinism); or the "small" tragedies that make up the life of the modern and civilized self.

It is no coincidence that he returned to Kafka and assumed the influence of this outsider of literature; hence his extraordinary book The Other Kafka Process (1969), an essay in which, from the letters of the Czech writer, he contrasts the figure of power represented by the father and the awareness of the limitations of the individual himself. Also, more distantly, that masterpiece entitled Auto de fe (195), the only novel written by the author, in which he returns to his obsessive vital reflection on the "heart of darkness" that inhabits the human being, that dark presence of power and evil.

The awareness of the fear and destruction that power entails is precisely one of the constants that permeate Canetti's work. A tale of power that often borders on delirium and sleep, built on a moral and almost metaphysical tension, in which power is seen as an evil that corrodes human nature. The result of this profound awareness is his book Mass and Power, the capital work of Canetti's production, conceived as the mission of his life, which began in 1925 and ended in 1960. In this book, with its interpretative and narrative brilliance, he delves into the somatic, anthropological and pathological entrails of power as an individual and social phenomenon.

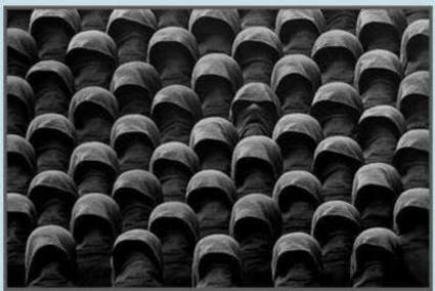

When we open Mass and Power we are surprised by a stinging phrase: "Nothing man fears more than to be touched by the unknown". Canetti, the man who lived in strangeness, inaugurates with this assertion his aqueous exploration in the hidden geography of power, for which this supposes as drives against the other: fear, indifference, paralysis, aggression... For this reason he will say: "Only immersed in the mass can man redeem himself from this fear of contact". The mass is undifferentiated, and in that trap or illusion of equality, he feels at ease.

When he tackles the case of Hitler (and National Socialism), which relied on the mass feeling of the Germans at the time, he managed, in turn, to make the Jews into a mass: "he directed his activity against the Jews as a whole," says Canetti. And he adds:

First they were attacked as bad and dangerous, as enemies; then they were devalued more and more; (...); in the end they were literally regarded as bugs that could be exterminated by the millions. Even today one is stunned that the Germans have gone so far, that they have carried out, tolerated or ignored a crime of such proportions.

Although the meditation and interpretation of power presented by Canetti in this work are not part of the conceptions on this question that came into vogue in the 80s and 90s developed by authors such as Michel Foucault or Jean Baudrillard, his vision penetrates areas of human behaviour that have not been addressed much, constituting what could be called a "phenomenological archaeology of power".

Let us read an extensive quotation from this book:

Whoever has climbed too quickly to the summit, or who has otherwise managed to appropriate the supreme command over such a system, by the nature of his position lives overwhelmed by the fear of command and must try to free himself from it. The continuous threat, which he uses and which constitutes the very essence of this system, finally turns against himself.

To discover in the mythological, historical and clinical account the veiled keys of the traditional experiences of domination, their symbolic behavior, the archetypes of their avatars, is undoubtedly a fundamental contribution that our current reflection cannot ignore. An expression such as the following referring to our time: "Power is greater, but it is also more fleeting than ever", brings it closer, without proposing it, to the most radical theses of the end of the century, such as those supported by Foucault in Microphysics of Power: "Power is everywhere".

Canetti, the Sephardic-Bulgarian-British, "disciple" of Franz Kafka and Karl Krauss, has bequeathed us a work and a consciousness that recovers for our sensibility the nourishing force of memory and encourages our dissidence in the face of power.

Bibliographical references

Canetti, Elías (1977). Mass and power. Spain: Muchnik Editores.

Written by @josemalavem

Click the coin below to join our Discord Server

)

I must admit with some embarrassment that I have not read Canetti, @josemalavem. The expressions and reflections that you make on his work, seems to me, as you say, very relevant in our times. I stop at the author's reflections on power, how it can not only corrupt, it also becomes a double-edged sword for the one who holds it, and especially for the one who achieves it without having forged it. A reading that becomes obligatory and pertinent so as not to make political mistakes and educate man. Thank you for sharing. Greetings

Canetti is an author of very pleasant writing when it comes to narrative texts (fictional or autobiographical), but very demanding in the case of essays or research texts, such as Mass and power (very voluminous book, by the way). It is really important to read it for civilizing reflection, to say it with a broad word. Thank you for your reading and comment, @nancybriti.

Hi, @adsactly!

You just got a 0.25% upvote from SteemPlus!

To get higher upvotes, earn more SteemPlus Points (SPP). On your Steemit wallet, check your SPP balance and click on "How to earn SPP?" to find out all the ways to earn.

If you're not using SteemPlus yet, please check our last posts in here to see the many ways in which SteemPlus can improve your Steem experience on Steemit and Busy.

Very interesting piece. I thought for a while that Canetti was Argentinean. For some reason his name sounded argentinean to me (I should have thought italian, but there are so many italian last names in argentina). I read some of his essays and I felt he was closer to us (latin americans; maybe latin american writers had been too europeanized and we were perceiving as ours what in reality was a european mentality)

I am not sure about this:

We have seen in the examples of Russian, North Korea, Cuba, Siria and some other gems how power, especially of the oppressive kind, can actually outlive those who fight it

Hello, @hlezama. I don't know if you can be confusing yourself with Cappelletti, who was an Argentine author.

The phrase you allude to is very interesting. Canetti writes it in the epilogue of the book. Of course, it is decontextualized, being extracted from the paragraph. He refers to the figure of that power (tyrannical, totalitarian) as a survivor. I will quote a little more:

This Canetti book was finished in 1959; the fall of Hitler, Mussolini, Stalin was already past... He never experienced the collapse of (in what a way!) Ceaușescu, Gaddafi and Hussein, among others, in which what he thought would also be fulfilled.

Thank you for your comment.

Congratulations @adsactly!

Your post was mentioned in the Steem Hit Parade in the following category:

Thank you, @arcange.